Early in the Salzmann Library lecture he delivered at Saint Francis de Sales Seminary April 19, Msgr. Thomas Olszyk posed a question.

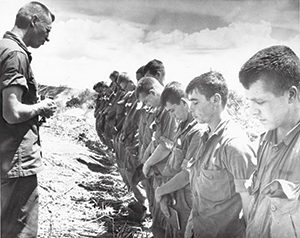

Maryknoll Fr. Vincent R. Capodanno, a Navy chaplain killed while serving with the Marines in Vietnam, is pictured ministering in the field in an undated photo. (CNS photo/courtesy Maryknoll Fathers and Brothers)

“Why does the church recognize people as saints?,” asked the canon lawyer and senior priest of the Milwaukee Archdiocese.

During the presentation titled “The Recognition of Saints,” he explained that the canonized might “serve as models for the Christian person to emulate. Models and intercessors.”

An Air Force chaplain for 23 years following assignments at two Milwaukee parishes, and subsequently judicial vicar for the Archdiocese for the Military Services, Msgr. Olszyk noted he’s been “working for several years” on the cause for sainthood of Maryknoll Fr. Vincent Capodanno, a chaplain killed while ministering to Marines during a 1967 battle in Vietnam who was posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Msgr. Olszyk has been serving as promoter of justice, more commonly called “devil’s

Msgr. Thomas Olszyk (File photo)

advocate,” in the cause. He described that role as “going on interviews basically to poke holes”– to pose tough questions that might temper the positive side of the candidate’s story that other investigators have been charged with developing.

From 2013-2015, Msgr. Olszyk and two other priests with backgrounds as military chaplains assigned to the cause interviewed relatives and friends of Fr. Capodanno. Among the interviewees were Fr. Capodanno’s nonagenarian sister, classmates, other priests and Marines – some of whom were present when the Maryknoller died. Msgr. Olszyk said he’s found the work, which could be completed by year’s end, “an exciting and humbling experience.”

While it may be common knowledge that canonization requires one or more miracles be attributed to the prospective saint, “the rest of the process is shrouded in mystery,” according to Msgr. Olszyk.

Briefly, the process begins with recognition of the prospective saint by a group.

“The important thing is (a sainthood candidacy) has to be promoted by a group,” Msgr. Olszyk said.

If a candidate had been a nun, a natural group would be the religious order to which she belonged. A candidate is first called a “servant of God,” as is the case with Fr. Capodanno; he or she will typically be declared “venerable” and then “blessed” en route to canonization.

The bishop of a diocese affiliated with the servant of God appoints a tribunal, which works clandestinely. Theologians inspect the servant’s writings to ascertain whether they are in tune with church teaching. Interviews are conducted with individuals who knew or were affected by the servant.

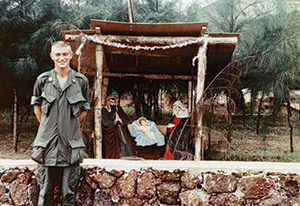

Maryknoll Fr. Vincent R. Capodanno is pictured in an undated photo. (CNS photo/courtesy Maryknoll Fathers and Brothers)

Documentation is sent to the Vatican, where a postulator, usually a layperson for whom such work is a livelihood, is appointed to advance the cause. A biography of the candidate, which may be quite lengthy, is compiled.

The prospective saint’s body will often be exhumed. While evidence of decomposition need not end the cause, an intact body might well lend credence to a candidacy. A medical commission is appointed to consider miracles attributed to the candidate; one martyred for the faith or for some aspect thereof – Archbishop Oscar Romero of San Salvador, for example, beatified in 2015, who died in service to the poor – needs to be credited with just one miracle. A miraculous cure must have been instantaneous, as well as being inexplicable to the medical team.

Finally, the cause for sainthood reaches the Holy Father.

“Not all causes presented to a diocese are sent on,” Msgr. Olszyk said. “Not all venerables become blessed. Not all blessed become saints.”

Kateri Tekakwitha, the “Lily of the Mohawks,” did become a saint – the first Native American to be canonized. However, the monsignor noted, St. Kateri, who died in 1680, “was venerable for years and years and years” prior to her canonization in 2012. By contrast, Mother Teresa of Calcutta will become St. Teresa this Sept. 4, 19 years after her death. St. John Paul II was declared a saint in 2014, just nine years after his passing.

According to Msgr. Olszyk, the first known canonization was that of St. Udalric, bishop of Augsburg, by Pope John XV in 993. There was no formal process for naming saints before then, the monsignor said.

Causes for sainthood which seem to have stalled include those of Capuchin Fr. Solanus Casey, a one-time Saint Francis de Sales Seminary student who, said Msgr. Olszyk, “apparently had the gift of healing,” as well as prophetic ability. Another is television preacher Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen.

In a cause begun by Fr. Casey’s order, the miracle aspect has unexpectedly proven problematic. In the second, the monsignor said, a “tussle” over exhumation between the archbishop’s home Diocese of Peoria, champion of the Sheen cause, and the Archdiocese of New York where he is interred has become a stumbling block.

During the question and answer session, Msgr. Olszyk noted “a lot of priests basically canonize people during the funeral Mass.” He said he considers this practice “way out of kilter” since “the theology of the church is that we pray for the souls departed” and the Liturgy of Christian Burial says nothing about the one for whom it is celebrated being a saint.

Who was Fr. Capodanno? MOH recipient drawn to mission work

When a priest is assigned to act as promoter of justice, or devil’s advocate, in a cause for sainthood, he is filling a position on behalf of the church and is not necessarily opposed to the candidacy of a possible saint.

That seemed obvious as Msgr. Thomas Olszyk spoke of Servant of God Fr. Vincent Capodanno during the Salzmann Library spring lecture.

Msgr. Olszyk, promoter of justice in the Fr. Capodanno cause, identified the military chaplain killed in Vietnam and posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor as “a model.” The monsignor distributed holy cards with the priest’s picture on one side and a “Prayer to Obtain a Favor Through the Intercession of the Servant of God” on the other.

Msgr. Olszyk pointed out that three “possibles” – possible miracles – have been attributed to Fr. Capodanno.

The priest summarized Fr. Capodanno’s life as well, telling his audience that Fr. Capodanno, who died at age 38 in 1967, was the youngest of nine children of Italian immigrants.

Feeling called to be a missionary after studying at Fordham University, Vincent entered a Maryknoll seminary in nearby Ossining, New York, and was ordained to the priesthood with 48 other men in 1958. He served in Taiwan, and then was assigned to teach at a Maryknoll high school in Hong Kong.

Disappointed with an assignment he did not view as a missionary endeavor, Fr. Capodanno sought and received permission to become a Navy chaplain.

He was assigned to serve Marines in Vietnam, requesting and receiving a three-month extension when his tour came to an end. He died on a battlefield where he’d been administering the sacraments and otherwise aiding Marines.

Schools, streets, Knights of Columbus groups and even a Navy ship were subsequently named for Fr. Capodanno.

After some two decades, a seminarian of the Diocese of Arlington, Virginia wrote a thesis on the chaplain after researching his life.

“The project took on a life of its own,” said Msgr. Olszyk, spawning a book titled “The Grunt Padre,” plus the assuming of the Capodanno sainthood cause by the Archdiocese for the Military Services.

The Maryknoll priest was accorded the servant of God appellation in 2002.