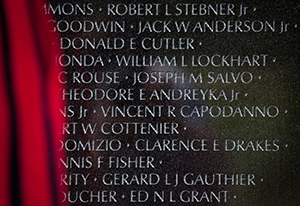

WASHINGTON –– When LaSalette Fr. Phil Salois visits the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, he always goes to panel 13 on the west side of the memorial and looks to lines 70 and 71. The name of Maryknoll Fr. Vincent R. Capodanno, a Navy chaplain who was killed while serving with the Marines in Vietnam, is seen on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington June 26. The names of 16 members of the clergy – seven Catholic, seven Protestant and two Jewish – are inscribed in the Wall, according to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund. This year marks the 30th anniversary of completion of the memorial. (CNS photo/Nancy Phelan Wiechec)

The name of Maryknoll Fr. Vincent R. Capodanno, a Navy chaplain who was killed while serving with the Marines in Vietnam, is seen on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington June 26. The names of 16 members of the clergy – seven Catholic, seven Protestant and two Jewish – are inscribed in the Wall, according to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund. This year marks the 30th anniversary of completion of the memorial. (CNS photo/Nancy Phelan Wiechec)

There he finds the names of Spc. Herb Klug and 1st Lt. Terrance Bowell, whose deaths in Vietnam March 1, 1970, changed Fr. Salois’ life forever.

Now chief of the chaplain service for the VA Boston Healthcare System and national chaplain of Vietnam Veterans of America, Fr. Salois was not a chaplain or even a priest when he and Klug ran into a firefight 60 miles northeast of Saigon to rescue several members of his unit in the Army’s 199th Light Infantry Brigade and to retrieve the body of Bowell, who had been killed in action.

It was then that Fr. Salois told God, “If you bring me back safe and sound, I’ll do anything you want.” He was one of only seven members of the 27-man unit who “didn’t receive a scratch” that day.

It took him a while to realize that God wanted him to become a priest and he was ordained in 1984. He has devoted much of his priesthood to helping veterans recover from post-traumatic stress disorder.

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial, marking its 30th anniversary this year, can be a big part of the healing process for survivors of the Vietnam War, in which more than 58,000 Americans died. About 4 million people visit the memorial each year, making it one of the most visited monuments on the National Mall in Washington.

Among those whose names appear on the black granite memorial designed by Maya Lin, then a Yale undergraduate architecture student, are eight women and 16 members of the clergy – seven Catholic, seven Protestant and two Jewish, according to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, the nonprofit organization authorized by Congress to build the memorial.

Perhaps the best-known Catholic chaplain on the memorial is Maryknoll Fr. Vincent R. Capodanno, a Navy lieutenant who was killed in 1967 while performing last rites for dying soldiers in Vietnam. His sainthood cause was officially opened in 2006.

But the list also includes two chaplains killed within nine days of each other — Marist Fr. Robert R. Brett, a lieutenant in the Navy Reserves who died Feb. 26, 1968, and Jesuit Fr. Aloysius P. McGonigal, a major in the Army Reserves, killed Feb. 17, 1968.

Fr. Michael J. Quealy, a priest of Archdiocese of Mobile, Ala., and an Army captain, died Nov. 8, 1966, and Cpl. George A. Pace, a seminarian studying for Archdiocese of Detroit and a Marine, was killed by mortar attack while serving Mass July 4, 1967.

But the Vietnam Veterans Memorial is as much about those who survived as it is about those who died.

Fr. Salois recalls coming back home to the now-closed Oakland Army Base in California in the middle of the night.

“They told us not to go home in uniform,” he said. His military haircut had grown out, he said, so he did not experience the scorn heaped on some returning veterans by those who opposed the Vietnam War.

But that did not mean he was untouched by his experiences in Vietnam. Although he “avoided watching that stuff,” he said news clips about firefights left him with an upset stomach and on the verge of tears. When others told their war stories, “much of the time I wanted to run out the door.”

Believing that there were others who could benefit from “talking over our war trauma through the eyes of faith,” Fr. Salois founded the National Conference of Vietnam Veteran Ministers, now known as the International Conference of War Veteran Ministers.

Years after his military service there, the priest decided to return to Vietnam with other veterans, hoping to “find a way to get over” his “real hatred and fear of the Vietnamese.”

It was not an easy trip. Fr. Salois found himself increasingly nervous as children flocked around the Americans in the streets. “But then I realized, I have no reason to hate these children,” he said. “They never knew what the war was like.”

He was also reminded of Jesus’ words: “Let the little children come unto me.”

Another breakthrough came when Fr. Salois was able to concelebrate a daily Mass in the Saigon cathedral. He believes he was the first American priest to celebrate Mass there after the end of the war.

During the Mass, he prayed to “find forgiveness for my contribution to the war and for the pain and suffering I caused.” As he looked out on the congregation he realized that “20 years ago I was here as a soldier killing people like this.”

The visit to Vietnam went a long way toward bringing healing to the priest and allowing him to forgive himself for being a part of the war. But there was more to do.

Over the next few years, he visited the families of Herb Klug and Terrance Bowell to recount his recollections of their final hours and arranged reunions that honored the memories of their lost colleagues.

But healing is a continuous process for Fr. Salois, as it is for many other war veterans.

He compares the process to putting together “a big jigsaw puzzle, broken up by different hurts and pains.”

“You have to have the patience of a saint, and there are still a lot of missing pieces,” he said. “It will never be a perfect picture and it’s not that pretty.

“But we can’t get rid of all the scars in our lives,” Fr. Salois added. “They remind us of where we’ve been.”