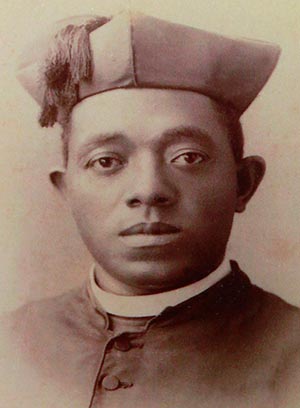

CHICAGO — With prayers, songs and sealing wax, Cardinal Francis E. George of Chicago formally closed the investigation into the life and virtues of Fr. Augustus Tolton Sept. 29 in a ceremony in the St. James Chapel at the Archbishop Quigley Center. Prayer card promotes canonization cause of Fr. Augustus Tolton. (CNS photo/Karen Callaway)

Prayer card promotes canonization cause of Fr. Augustus Tolton. (CNS photo/Karen Callaway)

The prayer service marked the binding and sealing of the dossier local research aimed at making Fr. Tolton, the first African-American diocesan priest, a saint. Cardinal George opened the cause in 2010.

Now the cause for Fr. Tolton’s canonization moves to the Vatican, where the documents collected by supporters of his cause in the Archdiocese of Chicago will be analyzed, bound into a book called a “position,” or official position paper, and evaluated by theologians, and then, supporters hope, passed on to the pope, who can declare Tolton “venerable” if the pope determines he led a life of heroic virtue.

Auxiliary Bishop Joseph N. Perry, the postulator of the cause, said the collected evidence – which includes everything from newspaper articles to correspondence to eyewitness testimonies – certainly indicates that is the case.

“Everything in the record of the case demonstrates that we had a saint among us and we hardly noticed,” Bishop Perry said. “Fr. Tolton leaves behind a shining example of perseverance.”

He was born a slave in 1854 on a plantation near Brush Creek, Missouri. His father left to try to join the Union Army during the Civil War. In 1862, his mother escaped with her three children by rowing them across the Mississippi River and settling in Quincy, Illinois.

Young Augustus had to leave one Catholic school because of threats; he found a haven at St. Peter parish and school, where he learned to read and write and was confirmed at age 16.

He was encouraged to discern his vocation to the priesthood by the Franciscan priests who taught him at St. Francis College, now Quincy University, but could not find a seminary in the United States that would accept him. He eventually studied in Rome and was ordained for the Propaganda Fidei Congregation in 1886, expecting to become a missionary in Africa. Instead, he was sent back to Quincy, where he served for three years before coming to the Archdiocese of Chicago in 1889.

He spearheaded the building of St. Monica Church for black Catholics, dedicated in 1894, and died after suffering heat stroke on a Chicago street on July 9, 1897.

Springfield Bishop Thomas J. Paprocki, whose diocese includes Quincy, attended the ceremony, as did representatives of the Diocese of Jefferson City, Missouri, where Brush Creek is located.

Cardinal George, who is to retire when his successor, Archbishop Blase J. Cupich, is installed Nov. 18, called the opening of Fr. Tolton’s cause one of the most important, if not the most important, thing he has done in his more than 17 years as archbishop of Chicago.

“The church, over the centuries, has ordained many priests, most of them quite holy, in some ways, some in great ways,” the cardinal said.

Fr. Tolton was one such holy priest, who “devoted himself to his people, quietly and in his own way,” he said, despite great difficulties and setbacks.

“Virtue has consequences, and virtue is stronger than evil,” Cardinal George said. “History is what God remembers. The rest passes.”

During the ceremony, Bishop Perry thanked members of the Fr. Tolton Guild, who are working to move the cause forward; members of the historical commission, who examined the records of his life; and members of the theological commission, who examined his writings to make sure that they are free of doctrinal error.

Neither commission found any reason for holding the cause back.

“Fr. Tolton demonstrated himself to be humble yet courageous, faithful to his priestly vows, welcoming to both black and white,” Bishop Perry said.

If the pope declares that Fr. Tolton indeed led a life of historic Christian virtue and is to be called venerable, Bishop Perry said, the next step is to look for evidence of a miracle attributed to Fr. Tolton’s intercession. The dossier sealed Sept. 29 includes letters already written to Cardinal George telling of favors granted after praying for Fr. Tolton’s intercession, Perry said.

In general, one confirmed miracle is needed for beatification, and a second such miracle is needed for canonization.

Andrew Lyke, director of the archdiocese’s Office for Black Catholics and a member of the Fr. Tolton Guild, said he will continue working to spread the word about the cause. His office and the Augustus Tolton Pastoral Ministry Program at Catholic Theological Union sponsor pilgrimages to sites significant in Fr. Tolton’s life and ministry, both in Missouri and Quincy and in Chicago, and the guild encourages everyone to pray for the priests intercession for whatever their needs are.

At the moment, Fr. Tolton is among four African-American Catholics whose sainthood causes have been opened, Lyke said, and his office tries to draw attention to all four.

The others are Mother Henriette Delille, foundress of the Sisters of the Holy Family in New Orleans, who has been declared venerable; Mother Mary Elizabeth Lange, foundress of the Oblate Sisters of Providence; and Pierre Toussaint, who was brought to New York as a slave and later became a well-known philanthropist, also declared venerable.

“But of course I have a special place in my heart for Fr. Tolton,” Lyke said. “He has always been an inspirational historical figure, but I feel much closer to him spiritually since I’ve been praying to him every day.”

Martin is a staff writer with the Catholic New World, newspaper of the Chicago Archdiocese.