Though the volunteers of the Vigil Keepers ministry at St. Anne’s Salvatorian Campus in Wauwatosa are there to provide a supportive presence for dying residents and their families, they will tell you that their outreach is as much of a privilege as it is an act of service.

It’s not a ministry for which everyone is well-suited, points out longtime Vigil Keeper Margaret Scola. “Not everybody is comfortable doing this, and that’s OK,” she said. “But it’s such an important thing. It’s an honor to be with people when they’re doing something so, so important — which dying is.”

The mission of the Vigil Keepers, said St. Anne’s Chief Executive Officer Janet Krahn, is “to ensure that nobody is alone moments before they enter heaven.”

“Sometimes, family is unable to sit at the bedside of their dying loved one, as they live far away, or they cannot sit bedside 24 hours a day due to the incredible grief they are experiencing, or it is not a comfortable place for some people to be,” Krahn said. “Some individuals have no family or anyone that can sit bedside by them and see them through this last journey.”

That’s when nursing or pastoral staff will alert the family to the existence of the Vigil Keepers, who sign up for shifts at the bedside of the dying person. They do not provide any physical care for the residents, but they do provide a ministry of presence, and an assurance for both the resident and their family that they are not alone on this journey.

This fall, the Vigil Keepers are able to once again companion the dying residents of St. Anne’s after a hiatus made necessary by the COVID-19 pandemic, when volunteer personnel were not allowed on the campus. During that time, said Krahn, many employees made an effort to sit vigil with residents during the last moments of their life — but the return of a dedicated ministry for that purpose is welcomed by everyone.

Each volunteer has their own style of vigil keeping. Scola explained that she always introduces herself when she enters the room, whether or not the resident is conscious. “It’s important that they know somebody is there. I generally hold their hand or put my hand on their arm for most of the time. Maybe I’ll pray with them a bit, or sing with them a bit — but I also spend some time just being very silent with them.”

“My style is very tactile,” said Susan Baglien, who coordinates the ministry. “I will pray the rosary with the resident, winding it through both of our hands so we move through it together. We make up our own ‘mysteries’ from the pieces of their life — ‘this first mystery is the mystery of your birth’ — things like that.”

Baglien gleans as much information about the resident as she can from family, staff members and even items present in the room. “Paintings, photos, music, books can all be used as fodder for conversation,” she said. “If the resident is responsive, I may ask questions about where they lived, what they liked to eat, cook. Did they grow a garden, travel, have children? What work did they do? Sometimes I ask them if they are afraid. I talk to them even if they are non-responsive, as it is said hearing may be the sense that hangs on the longest.”

The Vigil Keepers ministry has been offered at St. Anne’s since the late 1990s, when the Sisters of the Divine Savior operated St. Mary’s Nursing Home and Convent on 35th and Center Street in Milwaukee. Begun by Dcn. Dennis Ferance, Sr. Maureen Hopkins, S.D.S., and Sr. Charitas Elverman, S.D.S., Vigil Keeping continued under the guidance of the pastoral care department and volunteer coordinators like Baglien when the sisters moved to the present St. Anne’s Salvatorian Campus.

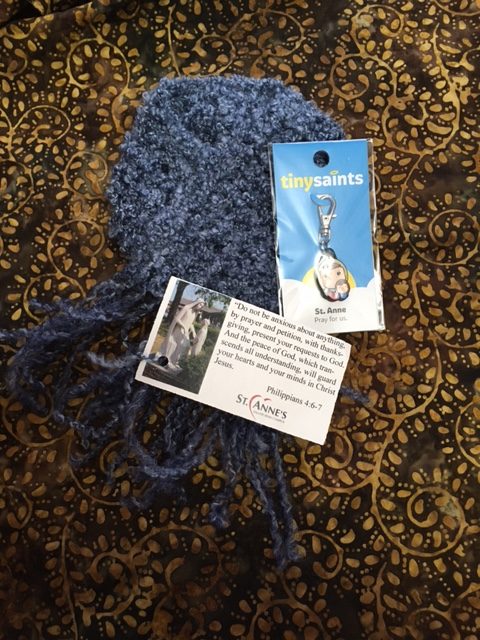

Oftentimes, the Vigil Keeper is the only one with the resident when they pass away. In those instances, Baglien said, the Vigil Keeper “maintains a prayerful presence for a few moments” before contacting staff, who then notify the family. A note from the Vigil Keeper is left for the family at the bedside along with a small keychain of St. Anne.

“Often the family will seek out that Vigil Keeper via phone or at the funeral service and want to ask how those last moments were,” said Baglien. “Sometimes, they want to hold your hand, as you were the last connection to their living loved one.”

She has been present at 13 deaths, and has sat at the bedside of 28 dying residents.

It is, she said, “an ethereal moment — when heaven and earth collide.”

There is, after all, no better way to learn about life — its value, its dignity and its brevity — than by bearing witness to death.

“It’s made me put things more in perspective. When you’re drawing your last breath, you’re not going to worry about your kitchen floor being clean,” Baglien said. “You learn to put your energy into your relationships. It’s made me think more about things in a relational sort of way.”