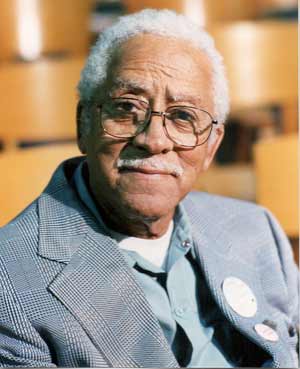

James Cameron’s near lynching is the subject of a one-man production, “10 Perfect: A Lynching Survivor’s Story,” performed by Patrick Sims, founding director of the Theatre for Cultural and Social Awareness at UW-Madison.” Cameron, a member of All Saints Parish, Milwaukee, until his death in 2006, received a Vatican II Award for Service to Society from Archbishop Rembert G. Weakland in 1996. (Catholic Herald file photo by James Pearson)When James Cameron was born, his mother, like most mothers, looked him over and cradled the most perfect being she had ever seen, admiring his 10 tiny fingers, 10 tiny toes, his head of dark hair and his high cheekbones. She also knew that, despite his perfection and similarity to any other newborn, it was 1914, and at that time, his race decided humanity’s actions.

James Cameron’s near lynching is the subject of a one-man production, “10 Perfect: A Lynching Survivor’s Story,” performed by Patrick Sims, founding director of the Theatre for Cultural and Social Awareness at UW-Madison.” Cameron, a member of All Saints Parish, Milwaukee, until his death in 2006, received a Vatican II Award for Service to Society from Archbishop Rembert G. Weakland in 1996. (Catholic Herald file photo by James Pearson)When James Cameron was born, his mother, like most mothers, looked him over and cradled the most perfect being she had ever seen, admiring his 10 tiny fingers, 10 tiny toes, his head of dark hair and his high cheekbones. She also knew that, despite his perfection and similarity to any other newborn, it was 1914, and at that time, his race decided humanity’s actions.

When Cameron was 16, he was falsely arrested and jailed in Marion, Ind. The teen was charged, along with two other black men, for robbing and killing a white man and raping that man’s girlfriend.

Hours after his arrest, an angry mob, led by the Ku Klux Klan, gathered and pulled the two others from jail; both were hanged outside while Cameron watched. The crowd returned for Cameron, shouting and beating him as they dragged him to the tree and strung him up with a noose tied around his neck.

Prepared to die, Cameron prayed to God to forgive his sins and to have mercy on him. Suddenly he heard an angelic voice that said, “Take this boy back, he had nothing to do with any killing.” While no one else heard the voice, the crowd died down, let him go and Cameron served four years in prison. He is the only known survivor of a lynching in U.S. history.

In 1988, Cameron, who was a member of All Saints Parish, Milwaukee, until his death in June 2006, started the former Black Holocaust Museum in Milwaukee, memorializing the victims of lynchings. It was there, in 1998, that Patrick Sims met Cameron – an encounter that led to his writing the one man production, “10 Perfect: A Lynching Survivor’s Story.” The play was performed for the first time in Milwaukee in late February at Cardinal Stritch University.

The play chronicles the life of Jimmy “The Salmon” Solomon. Born and raised in the heart of northern Ku Klux Klan territory, Solomon revisits his earliest memories as a child growing up with his best friend, Tommy, who is white. The story takes the boys into their tumultuous teen years, and abruptly changes Aug. 7, 1930, the night of the lynchings.

Sims, the founding director of the Theatre for Cultural and Social Awareness at UW-Madison, as well as associate professor of acting and head of the undergraduate acting specialist program in the department of theatre and drama, conceived the idea after several visits with Cameron.

“After I met him, I felt this immediate connectedness to him, and really was touched after hearing his story about being stupid and going out joyriding at 16,” he said. “His buddies robbed someone, and I realized that we all did stupid things in our youth and what would it have been like for me, if it was 1930 instead of 1992 when I was 16; it really hit close to home for me.”

Learning that his own grandfather nearly was lynched, as well as the stories he told about growing up a black man in those years, propelled him to research and write the story.

In the production, Sims plays the parts of 18 different characters, telling the story and honoring Cameron. He transforms from an older, thoughtful Cameron into a 6-year-old anticipating his future, to a doting mother, all in an effortless transition explained Sheri Williams Pannell, director of the production. She and her husband Don were also the show’s co-producers.

“In the beginning, he had 38 characters and cut it down to the 18,” she said. “He goes back and forth and while you might think it confusing, when you see his transition you have no problem understanding who is speaking, whether it’s children, men, women or elders.”

The directing challenge for Sheri was the pacing and helping Sims to maintain his stamina throughout the 90-minute play.

“We worked on clarity and length for each character and had to make sure the space was used well,” she said. “We don’t have a fully developed set in all the areas so there are places in the play that the audience fills in what’s missing by imagining what is happening along with our using lighting, sound and the actor to approximate what is going on with the story.”

As an established Milwaukee writer, performer and director, Sheri believed, after she read Sims’ play the first time, that it would touch and heal hearts.

“I told him that he must do the play, but I also knew that there was more to the story and it needed to be told. I asked questions and those prompted him to write more,” she said. “I believe that people will be very receptive and see how the truth resonates what fear and the language of hate can do to a community. I also believe it will offer the opportunity for healing through opening up conversation and recognizing an aspect of American history that has been buried.”

The truth is a lesson that Cameron taught to Sims during their lengthy visits, a truth that can be brutal, ugly, but courageous and an opportunity to open doors of healing and grace.

“You know, I expected animosity or hesitancy or reluctance, but Dr. Cameron embraced with open arms, and forgave everyone. He was a devout Catholic and his experience was the foundation of his faith,” said Sims. “After he was having his Golgotha experience in the jail cell, being kicked and punched, another sheriff took him and was kind and prayed with him, and that was the beginning of his faith and devotion to Catholicism.”

After his term in jail, he went on to be a passionate advocate for civil rights, combating racism and segregation, married and had five children. Employed as a boiler engineer, Cameron was also a self-taught historian who loved books and reading.

“These are things I never would have learned had I not followed the signs into the Black Holocaust Museum that day,” said Sims. “Here I was an Ivy League-educated black man, and I didn’t know who Cameron was – and once I met him, I knew his story needed to be told.”

Audience reaction to the play so far has been encouraging said Sims, who recently performed to a 500-member audience in Augusta, Ga.

“We expected 150 and had to open up two other ballrooms to accommodate all the folks who came to see the play,” he said. “I was floored, and it really made me feel like I am doing my job.”

While his Baptist faith is solid, exploring Cameron’s story and the touching stories of other Black Americans who lost family members to lynchings has not only taught him much about forgiveness, but also strengthened his faith.

“Just to tell the story requires faith, and really, after talking to Cameron, I knew that this was what God wanted me to do,” he said. “I was put on this earth to tell this story, and while the play has its challenges, it pales in comparison to what he went through, but there is joy in the morning and weeping at night – and I am looking forward to many mornings.”

In recognition of Black History Month in February, Rev. Trinette McCray, the executive director of the Center for Calling and Engagement at Cardinal Stritch, felt the production would be appropriate especially since Cameron served in a previous position at the university.

“He was the director of multi-cultural relations and received the Martin Luther King Peacemaker Award back in the mid 1990s,” said Rev. McCray. “We are all inspired of the life of Dr. Cameron and his partnering with the Black Catholic Commission on Ministry in the archdiocese and spreading the word through networks.”

As a Franciscan-based university, the values at Cardinal Stritch are punctuated by justice, peace and creating a caring community, explained McCray.

“Given what Dr. Cameron experienced, certainly Franciscan values would connect with this work to bring justice and peace in the community and world that wouldn’t provide that for him,” he said. “Franciscans are involved in urban areas and cities and connect as a message of peacemaking. Dr. Cameron made peace with abusers and peace with his self and circumstances and he extended that peace through telling the story for African American history to pursue peace and justice in a caring community, and that connects with the values at Stritch.”

“Dr. Cameron was a man of great faith and as he prayed, he understood that his being rescued from the lynching as Jesus coming himself and rescuing him,” she said. “That great faith through all circumstances is needed in our times and if we still hold on to it, would be a plus.”

As to what Cameron might think of the performance if he were here today, Sheri wells up with tears as she fondly remembers a comment from his son, Virgil.

“He saw the performance in Madison and came up to me afterwards,” she said. “He told me that his dad would be proud of this play and it brought tears to my eyes.”