COLLEEN JURKIEWICZ

CATHOLIC HERALD STAFF

In the video that captures the last moments of his life, George Floyd can be heard gasping: “Mama!”

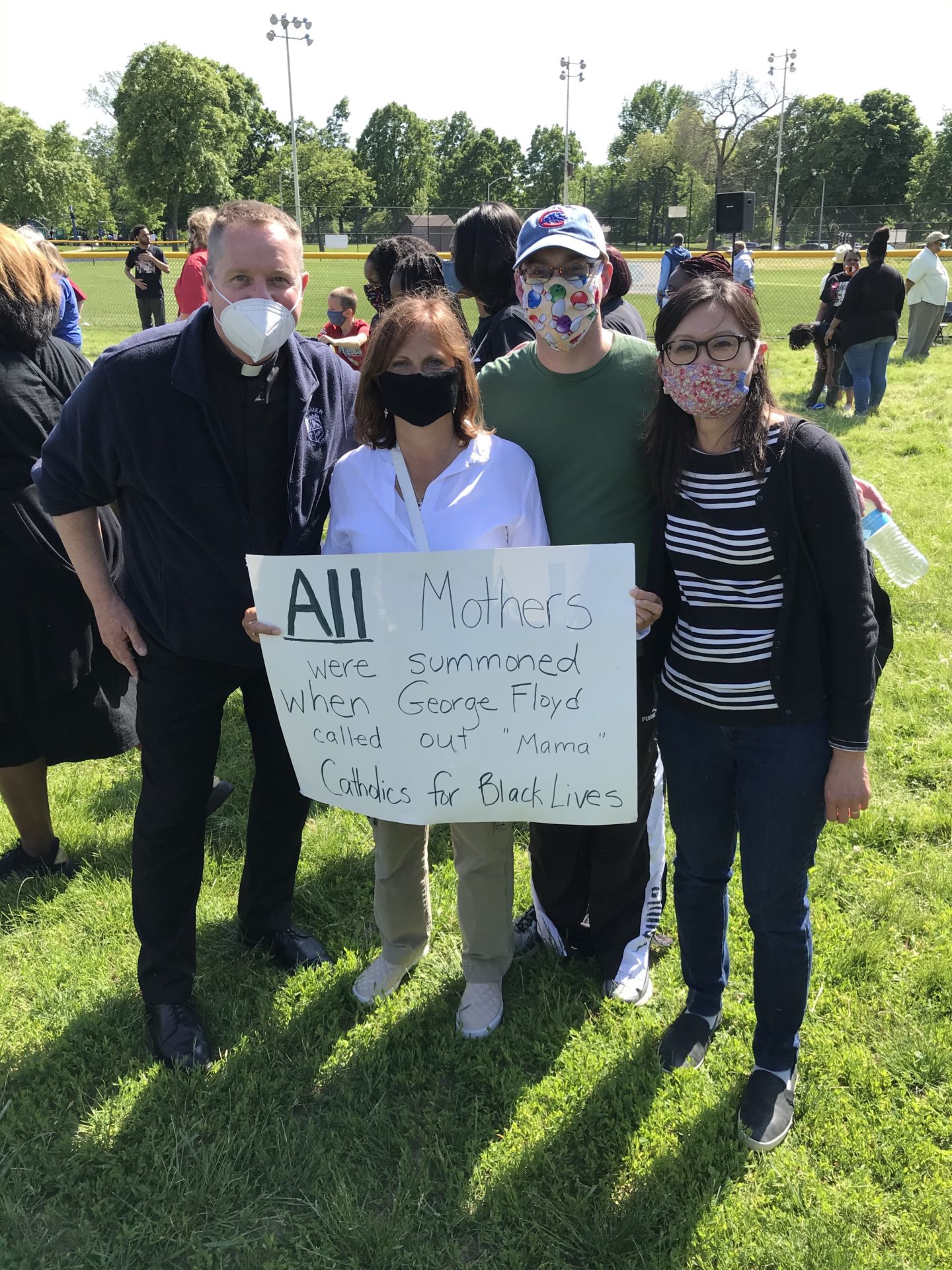

Fr. Tim Kitzke, Anne Haines, Chad Griesel and Anh Hoang Clausen at the Pastors and Mothers March. (Submitted photo)

When any dying person calls out for his mother, all mothers see their own child in the face of that dying person.

Certainly, preventing the death of Black human beings as the result of racism is work that will require a multifaceted approach and the cooperation of many levels of legislative, law enforcement and social entities.

But as Catholic moms, it’s work that also can — and has to — begin in our homes.

While many Catholic moms, particularly moms of color, do not get the privilege of choosing the moment their child first engages with the topic of racism, for many white Catholic families, the issue is, in fact, all too easy to ignore.

“If the system doesn’t serve people of color in just and dignified ways, we don’t see that because when you are white, the system typically works more easily for us,” said Shelly Roder, director of Franciscan Peacemakers Social Enterprise. “It’s hard to see it as a problem if you don’t experience it as a problem.”

Discussing issues surrounding racism has to be part of our work as Catholic moms, just as we address all pro-life issues with our kids. We must combat the anti-life narrative that is perpetuated by the evil one, who hates the God-given dignity of every human being, and who constantly works to undermine how we see that dignity in ourselves and in others.

“Jesus really saw people. He was profoundly engaged with people whose experience was outside the way he was raised,” said Laura Hancock, director of Social Justice and Outreach for Old St. Mary, Three Holy Women, Sts. Peter and Paul and Our Lady of Divine Providence parishes.

Roder is a mother of four, and Hancock is a mother of two. Both are white, and both readily admit that it isn’t always comfortable to engage on topics of race and racism with their kids.

But both believe that it is crucial for Catholic families to have these conversations about race and privilege. There are no easy answers, and it can be awkward to navigate — in fact, points out Roder, it should be, and feelings of discomfort are a good indication that you’re asking the important questions of yourself.

“In his helpful TedX talk, (cultural commentator) Jay Smooth points out that race was meant to be confusing,” said Roder. “It doesn’t make sense. When you feel confused about it, it’s because it’s meant to be that way. But there are consequences to race, which is why it’s important. When it brings up anxiety, that’s because it is designed to do that. If you can stay in the discomfort for a little bit of time, that means you’re moving through it.”

“We need to become more skilled at discomfort,” said Hancock. “We need to learn how to be patient in it, to observe our discomfort and to see what it has to teach us.

In discussing some ways their families approach the issues surrounding racism and privilege, Hancock and Roder had these reflections to share.

Anti-racism work is not a partisan issue.

This work is about one thing: following Christ more closely, and loving him better in our neighbor.

“When anti-racism work is called a political thing or labeled propaganda, it’s surprising, because to me it has been such a life-giving process of learning — or as (speaker and writer) Austin Channing Brown puts it — ‘how to be a better human to other humans’ — which is what Christianity is about,” said Roder.

Seeing color is fine.

It’s good, actually — God made us in different colors, so why would we teach our children to ignore that? “To say ‘I don’t see your color’— it can be dismissive of so much of what makes a person who they are,” said Hancock. It is also appropriate to discuss the broader picture of how color has a real impact on how people move through the world, the barriers they run into, their experience of justice, and the resources they can and cannot access.

Listen to the lived experiences of people of color.

The only way for white families to understand the experiences of their Black brothers and sisters is to listen to them. But at the same time, it is not the responsibility of people of color to give white people an education in racial sensitivity.

“It’s an interesting paradox of needing to listen primarily to voices of color from people who have so much to teach us — but at the same time, it’s not the person of color’s responsibility to actively teach us,” said Hancock.

“In today’s age of information, there are countless sources for online education and ways to get informed,” said Roder. “Diversify your bookshelves and your media content as one very simple place to start.”

Share information with your kids, but don’t assign blame.

You may have to be selective about what details to share or how to phrase things, based on the child’s age and personality — but “they want to know information, and they want us to be with them as they walk through the information,” said Hancock. Follow up with questions: how does this information make you feel? What does it make you think?

Hancock also said that her children have shared that attitudes of blame and judgment are unhelpful. “Assume best intention or assume ignorance,” she said. “Whatever they’re feeling, it’s an opportunity to learn, an opportunity to change.”

Put aside your ego.

“We’re struggling and making mistakes all the time,” said Hancock. If, as a white person, despite sincere efforts to learn and practice respect, you still make a mistake and are corrected by a person of color, Hancock encourages people to take it “as a gift, and a gift of love.”

“It’s all part of learning,” she said. “The world won’t end.”