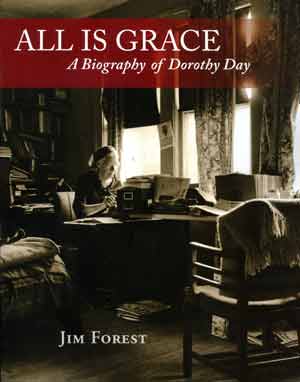

“All Is Grace: A Biography of Dorothy Day” by Jim Forest. Orbis Books (Maryknoll, N.Y., 2011). 352 pp., $27.

“All Is Grace: A Biography of Dorothy Day” by Jim Forest. Orbis Books (Maryknoll, N.Y., 2011). 352 pp., $27.

Jim Forest, an author, peace activist and secretary of the Orthodox Peace Fellowship, first met Dorothy Day (1897-1980) in 1960. Forest’s affection for and knowledge of her life and work inform “All Is Grace,” a carefully crafted and insightful book that significantly revises and expands his 1986 biography, “Love Is the Measure.”

Forest is an accomplished writer and his fluent prose is a pleasure to read. He confines his personal remembrances to the book’s final chapter, an evocative portrait of Day’s gratitude, faith, painful self-knowledge, disciplined prayer life and the ability to be “as fierce and determined as one of those resolute Russian women who repaired Moscow streets and kept going to church even in the years of Stalin.”

“All is Grace” is a physically beautiful book, the skilled work of designer Roberta Savage. Slightly oversized, each page of the book has a block of text and, in the wide margins, either a photograph or excerpts from Dorothy Day’s writing. (Forest frequently quotes from 2008’s “The Duty of Delight: The Diaries of Dorothy Day” and “All the Way to Heaven: The Selected Letters of Dorothy Day,” published in 2010. Both volumes were edited by Robert Ellsberg and published by Marquette University Press.)

“All is Grace” contains more than 200 black-and-white photographs, many from the Marquette University archives. There are photographs of Day as a young girl and a young mother, in the early years of the Catholic Worker, and as a strikingly attractive mature woman.

There are photographs of the important people in her life: her siblings and Forster Batterham, the father of their daughter, Tamar, and the man with whom she knew, for too short a time, domestic happiness. There are many photographs of Tamar, from her infancy and childhood to her own years as a wife and mother. Catholic Workers are here, including co-founder Peter Maurin and longtime friends like Eileen Egan, Ammon Hennacy, Fr. Daniel Berrigan and Blessed Mother Teresa of Kolkata.

There are photographs of the places and events that were important in Day’s life: Kings County Hospital, where she trained as a nurse in 1918; St. Joseph’s Church in Greenwich Village, where she stopped to pray in the first inklings of her religious call; the farms and houses of hospitality in which she lived out her vocation.

The photographs and quotes from her writings anchor Forest’s text and serve as a visual complement to the skillful way he situates Day in her religious, political and cultural contexts. He provides sufficient, but not laborious, detail so that the reader understands what and who influenced Day, and what and who she influenced.

Day made the momentous journey “from Union Square to Rome” (as she titled the narrative of her conversion) but as Forest illustrates, there was also a lot of consistency in her life. She belongs to the tradition of an indigenous American radicalism, beginning with her 1917 arrest as a suffragette, being shot at while standing in solidarity with the Koinonia community in 1957, resisting civil defense drills in the 1950s, opposing the Vietnam War in the 1960s, to her final arrest and two-week jail sentence in 1973, in solidarity with the United Farm Workers union.

The accumulation of details and insights that accrue from Forest’s carefully chosen and illustrative anecdotes weaves a seamless portrait of Day that mirrors her profound incarnational sensibility. Excerpts from her writings reveal the almost palpable delight she took in the physical, sensual world, qualities that infused her distinctive prose style with warmth and clarity. She loved opera (Wagner was her favorite composer) and Russian novelists, especially Dostoevski. She practiced a rigorous voluntary poverty but did not starve her senses. Once, Forest writes, “she discovered chopped onions, herbs and spices in the fruit salad.” “A sacrilege,” she wrote, “to treat food this way. Food should be treated with respect, since Our Lord left himself to us in the guise of food. His disciples knew him in the breaking of bread.”

Day often quoted Dostoevski that “beauty will save the world.” In both its text and in its luminous photographs “All is Grace” offers a vivid testimony to Day’s beauty, fidelity and, in the midst of suffering and hardship, a stunning witness of perseverance and hope.