For many families, a highlight of the Christmas season is putting together their nativity set. Everyone takes part, and often the youngest child gets to put the Baby Jesus in the manger, though perhaps not until Christmas Eve.

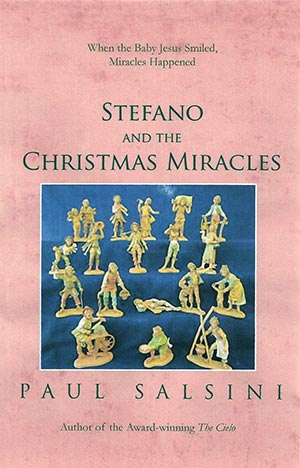

“Stefano and the Christmas Miracles,” by Paul Salsini, published by CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (Oct. 11, 2012); 126 pages. Weeks before Christmas, little Stefano sits down with his grandfather Nonno and they begin to put together their Nativity scene, or presepio, adding one figure each day. Nonno tells Stefano the amazing story of each of the miniature people and about the wondrous miracles that happen when they visit the Baby Jesus.When I was writing my new book for children, “Stefano and the Christmas Miracles,” I did some research about the history of Nativity sets (crèche in French, presepio in Italian, szopka in Polish, Weihnachtskrippe in German).

“Stefano and the Christmas Miracles,” by Paul Salsini, published by CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (Oct. 11, 2012); 126 pages. Weeks before Christmas, little Stefano sits down with his grandfather Nonno and they begin to put together their Nativity scene, or presepio, adding one figure each day. Nonno tells Stefano the amazing story of each of the miniature people and about the wondrous miracles that happen when they visit the Baby Jesus.When I was writing my new book for children, “Stefano and the Christmas Miracles,” I did some research about the history of Nativity sets (crèche in French, presepio in Italian, szopka in Polish, Weihnachtskrippe in German).

It was a fascinating history. I found that the first known image of the Nativity scene dates back to the first half of the third century. In a now-faded fresco in the Catacombs of Priscilla in Rome, Mary holds the Baby Jesus on her knees and a man stands nearby. The man could be Joseph, but scholars believe it is more likely a prophet, Balaam or Isaiah, because he is pointing to a star, presumably the Star of Bethlehem.

In the following centuries, other frescos were painted in catacombs. One in the Catacomb of St. Sebastian doesn’t show Mary or Joseph, but there’s a manger and a donkey and an ox. Then, in the fourth and fifth centuries, the figures of Mary, Joseph and the Baby Jesus were carved in bas-relief on marble sarcophagi.

In Italy, the first presepio is attributed to the sculptor Arnolfo di Cambio, built around 1289 for the Basilica of St. Mary Major in Rome (which also contains pieces of wood allegedly from the original manger). Some of the marble figures have been lost, and only the original Joseph, three kings and the ox and donkey survive.

St. Francis has often been called the father of the nativity scene and it is true that, in 1223, he famously created a “living” representation of the scene with at least a donkey and an ox. Francis was visiting the village of Greccio in Umbria at Christmas time, and finding the Franciscan chapel there too small, he decided to celebrate Midnight Mass on the town square. He produced a scene of the Nativity that, according to legend, also had real people dressed in biblical robes with a wax figure of the Baby Jesus in the manger.

That may not be entirely true. In a biography of Francis written 37 years after the saint’s death, St. Bonaventure, himself a Franciscan, says only that Francis “prepared a manger, and brought hay and an ox and an ass to the place appointed.”

There’s no mention of people, but Bonaventure also says: “The hay of that manger, being preserved by the people, miraculously cured all diseases of cattle, and many other pestilences.”

Whether that first living crèche scene was elaborate or not, the idea of having real people enact the Bethlehem story grew, and it was a popular subject in medieval mystery plays. When these got out of hand, the Catholic Church declared that only static representations of the Nativity should be permitted.

Italian craftsmen responded with wooden presepi in the 14th and 15th centuries and members of the della Robbia family created many images of the Nativity scene in terracotta.

But it was in Naples in the 18th century that the presepio achieved its greatest glory. King Charles III set the example by building an elaborate scene in the palace, and wealthy families followed suit. The displays consisted not only of the traditional Mary, Joseph, Baby Jesus, shepherds, angels and kings, but also fantastic market scenes crowded with merchants, butchers, shoppers and fishermen. Unfortunately, the Baby Jesus, Mary and Joseph were sometimes lost in these bustling panoramas.

Although these sets are now mainly in private collections and museums, the House of Fontanini in Tuscany continues the Neapolitan marketplace tradition, turning out figures of ordinary people doing ordinary things – a woman with a duck, a man with a sack of grain, a man who looks like a beggar, a farmer holding a basket, a boy playing a reed-pipe, and on and on, dozens of them.

In my book, a grandfather tells his grandson the story of each of the figures in their manger scene, how they went to see the Baby Jesus and the miracles that happened to them there.

When I look at the figures in my Nativity set each Christmas, I wonder if they represent real people who visited the Baby Jesus in the manger. Who’s to say they did not? After all, the Bible can’t tell us everything that happened that glorious night, and isn’t Christmas a time for believing in miracles?

(Salsini, who teaches journalism courses at Marquette University, is the author of four novels set in Tuscany. “Stefano and the Christmas Miracles” is available at Boswell Books, Stemper’s and the Marian Center in Milwaukee, Amazon.com and other online distributors.)