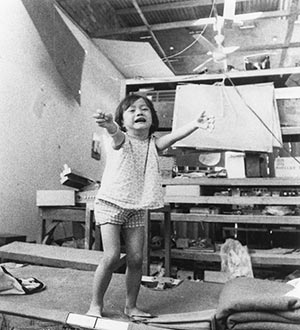

WASHINGTON — Forty years after the war in Vietnam ended, Americans still replay the events that led to deeper American involvement in the Southeast Asian conflict as well as the turmoil that resulted from it. A girl cries after a rocket destroyed her home in 1973 during the Vietnam War on a U.S. airbase in Bien Hoa, South Vietnam. Forty years after the war in Vietnam ended, Americans still replay the events that led to deeper American involvement in the south east Asian conflict, as well as the turmoil that resulted from it. (CNS file photo)

A girl cries after a rocket destroyed her home in 1973 during the Vietnam War on a U.S. airbase in Bien Hoa, South Vietnam. Forty years after the war in Vietnam ended, Americans still replay the events that led to deeper American involvement in the south east Asian conflict, as well as the turmoil that resulted from it. (CNS file photo)

Satisfactory answers were hard to come by then, when it seemed that the nation came close to tearing apart at the seams. The lessons to be learned from Vietnam can still be difficult to hear, much less understand and accept.

David Cortright, director of policy studies at the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies at the University of Notre Dame — and a Vietnam dissenter while serving stateside in the Army outlined three hard lessons.

“One is what I would call ignorance of the conditions we were addressing,” he told Catholic News Service May 7. “We had no idea what was going on in Vietnam when we went over there. Very few (U.S.) people spoke the language. We didn’t know the culture.”

Cortright’s second lesson was “arrogance. We believed that our military was invincible. We believed we could just push aside these peasants, and bombed enough and sent enough troops, they would certainly submit to our will. We underestimated the tenacity and the willingness of these people to suffer unbelievable losses and destruction and casualties.” The fighters from North Vietnam “wanted to unite their country and be free of foreign rule and foreign orders,” he said. “So our arrogance was born out of our ignorance.”

The third lesson was the lack of “any kind of reliable partner on the ground in terms of the Saigon government,” Cortright said. “It was a corrupt government. There was a revolving door of different leaders in the Sixties. Generals kept coming and going. The South Vietnamese government was never legitimate in the eyes of the people there, except for a small percentage. They were based pretty much in the Catholic community, the Saigon government. But the Catholic community is less than 10 percent of the population. … You can’t build an alternative to the communists if you have only 10 percent of the population.”

Cortright told CNS, “What really gets me is how little we seem to have learned. We fast-forward 40 to 50 years. We went into Iraq with little idea of what was going on. When the occupation authority was set up in ’03, reportedly just a dozen officials spoke passable Arabic. We didn’t know all the differences between Sunnis and Shias and all the different tribal groups there. The ignorance and the arrogance.

“You could say the same thing in Afghanistan. We didn’t know the people or the culture. We had even fewer people who could speak Pashto. We didn’t have reliable partners. The regimes in Iraq and Afghanistan have been corrupt and don’t have much authority in the country. The same kind of ignorance and arrogance and lack of a reliable partner are continuing those problems in our military policy today,” Cortright said.

America’s sense of obligation to the South Vietnamese who were defeated in the war was a hit-or-miss proposition.

The BBC reported in its own 40-year Vietnam retrospective that actress Tippi Hedren, best known for her role in the Alfred Hitchcock movie “The Birds,” was so moved by her visit to a Vietnamese refugee camp in California that, in looking for vocational opportunities for the women, flew in her personal manicurist to teach 20 of them how do to manicures.

Those 20 women revolutionized the industry. The BBC estimates that slightly more than half of all manicurists in the United States are of Vietnamese descent – 80 percent in California – and the industry is now worth about $8 billion.

“Of course I know who Tippi Hedren is! She’s the godmother of the nail industry,” said Tam Nguyen, president of Advance Beauty College, which was started by his parents, both of whom were trained by Hedren.

Hedren now operates a wildcat sanctuary at her home in Southern California. “I sure wish I had a percentage” of the Vietnamese nail technicians’ take, she said. “I wouldn’t be working so hard to keep these lions and tigers fed.”

But not all refugee assistance went as smoothly, despite the best intentions. Mary Ellen Koyle, a single mother of two pre-teen children who was the adult adviser for her parish’s teen club in Detroit when the war ended, took in a refugee family. One mishap was followed by another.

On the first night the family arrived, the youth group came over to give them an American welcome. “That group of people were so amazing, but guess what they fixed. Hamburgers. I don’t think the family ever saw a hamburger because they tried to eat it with chopsticks,” Koyle recalled.

The next night, she added, one of the family’s young sons ran away. “It must have been so overwhelming for them,” Koyle said. The boy was found within an hour. The other son had been born with an extra thumb. The parish’s Christian service coordinator found a surgeon who removed it for the boy. “He was real shy in meeting people,” she remembered.

Koyle bought a big burlap bag of Vietnamese rice, thinking it would provide a taste of home for the family, but they shied away from eating it whenever she cooked it. It turned out it was the kind of rice the Vietnamese fed their pigs.

“I have often – many, many, many times – thought of this family,” Koyle said. “It was very traumatizing for them. I knew nothing about their culture, nothing about their language, nothing about their food, nothing about being Vietnamese.”

She added, “It was also very traumatizing for my kids. I wish I had enough knowledge or whatever to understand what was happening to them. I was just trying to help people who had no place else to go.”

The war era was roiled by protests at the White House, city streets and college campuses.

“If you’re asking what lesson the political establishment draws from this, it’s don’t send a citizen army into a war which many people are questioning, if not downright opposed,” said Notre Dame’s Cortright. “The answer: Go to a volunteer army. But are we better off?”

Today’s all-volunteer army are from “rural, poor neighborhoods where there’s not much opportunity,” he added. “We don’t have a forced draft, but we have a kind of economic draft. People say it’s not a poverty draft, but it’s a draft in the sense that lower (class) working families, those with fewer opportunities, go to the military because it’s a place where some opportunity exists. Families don’t have the means to send them to college.”

As Cortright said one ex-soldier told him, “It was either Ronald McDonald or Uncle Sam.” The irony that Cortright’s job is funded by McDonald’s money is not lost on him.

“Ray Kroc (who built the McDonald’s empire) was a real conservative, but his widow, Joan, met (Fr.) Theodore Hesburgh (Notre Dame’s then-president), and agreed on the study of peace at a great university and she provided the means,” Cortright said. “So we’re truly blessed.”