NEW YORK – Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan, an early critic of U.S. military intervention in Vietnam who for years challenged the country’s reliance on military might, died April 30. He was 94.

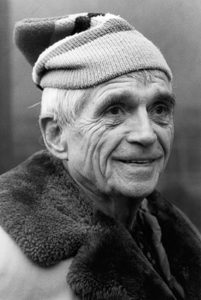

Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan, an early critic of U.S. military intervention in Vietnam who for years challenged the country’s reliance on military might, died April 30 at 94. He is pictured in an undated photo. (CNS files)

The author of several books of poetry and one of the first Catholic priests to receive a federal sentence for peace activism, Fr. Berrigan protested government policies in word and in deeds, which garnered several stays in jail and in federal prison.

Fr. Berrigan died in the company of family. In a statement issued shortly after the priest’s death, the family said, “It was a sacrament to be with Dan and feel his spirit move out of his body and into each of us and in the world.”

“Dan taught us that every person is a miracle, every person has a story, every person is worthy of respect,” the statement said. “And we are so aware of all he did and all he was and all he created in almost 95 years of life lived with enthusiasm, commitment, seriousness and almost holy humor.”

The “heavy burden” of peacemaking will continue among many people, the family added, saying, “We can all move forward Dan Berrigan’s work for humanity.”

A funeral Mass was planned for May 6 at St. Francis Xavier Church in New York. Family members and others were to gather prior to the Mass for a peace witness followed by a march to the church.

A poet whose works inspired people reflect and act on behalf of justice and peace, Fr. Berrigan began speaking against U.S. military involvement in February 1965 at a rally in a Protestant church in New York City.

“To men of conscience, such works cry out to heaven for redress. They also sow into man’s future a poison which the unborn will be condemned to breathe — hatreds, divisions, world poverty, hopelessness. In such an atmosphere, the world comes ever closer to the actuality of hell,” Fr. Berrigan told the crowd.

He told various groups and retreats he led over the years that Catholics are called to live a life of nonviolence as expressed in the Gospel and to protest injustices when they are encountered.

Fr. Berrigan, with others, gave birth to the Plowshares movement to oppose nuclear weapons. On Sept.9, 1980, Fr. Berrigan, his brother Philip, and six other demonstrators were arrested after entering the General Electric missile plant in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, and battering intercontinental ballistic missile nose cones with hammers and pouring blood over classified defense plans.

Calling themselves the “Plowshares Eight” from the biblical passage, “And they shall beat their swords into plowshares,” the eight defendants were tried in the Montgomery County Common Pleas court, where the presiding judge rejected the use of international law theories of justification for an illegal act. They were found guilty of burglary, criminal mischief and criminal conspiracy and sentenced in July 1981. The Berrigan brothers, Oblate Father Carl Kabat and Baltimore lawyer John Schuchardt received the stiffest sentences, three to 10 years in prison.

The protest was the second major action for which he was arrested. On May 17, 1968, Fr. Berrigan and eight others entered the Selective Service office in Catonsville, Maryland, a Baltimore suburb, removed 378 files and burned them in an adjacent parking lot with what they called “homemade napalm.”

The “Catonsville Nine,” as they called themselves, were tried for conspiracy and destruction of government property in U.S. District Court in Baltimore in October 1968. Fr. Berrigan testified that he participated in the burning because he had come to realize that “one simply cannot announce the Gospel from his pedestal … when he was not down there sharing the risks and burdens and the anguish of his students.”

While the presiding judge told the defendants he was moved by their views and was anxious to terminate the war. “But people can’t take the law into their own hands,” he said before finding the defendants guilty. They were given sentences ranging from two to three and a half years in jail. Sentenced to three years, Fr. Berrigan was ordered to surrender to federal authorities and begin serving his sentence on April 10, 1970. Instead, he went underground, evading federal agents for four months.

The Jesuit surfaced occasionally during those months. In addition to a handful of public appearances at churches and schools, he published articles in several magazines.

FBI agents eventually arrested Fr. Berrigan on Block Island in Long Island Sound and he was sent to the federal penitentiary in Danbury, Connecticut. In January 1972, the Federal Parole Board granted Fr. Berrigan parole for “reasons of health” and he left prison Feb.24.

Fr. Berrigan’s views at times led him into conflict with other opponents of U.S. involvement in Vietnam and even raised the ire of some leaders in the Catholic Church.

Daniel Berrigan was born in Virginia, Minnesota, May 9, 1921, the fifth of six sons of Thomas Berrigan, a second‚ generation Irish‚ American who was working there as a railroad engineer, and Frieda (Fromhart) Berrigan, who was of German descent. Fired for militant Socialist Party activity, the father moved the family to his birthplace, Syracuse, New York, where they lived on a 10‚ acre farm.

Because he was frail and had weak ankles, Daniel was assigned to do household chores while his brothers tilled the soil under the supervision of their father. Mrs. Berrigan was a devout, generous woman, always ready to feed and house the needy. “From the age of 6, Daniel was obsessed by the suffering in the world,” she later recalled.

Attracted to the priesthood from his earliest years, he sent inquiries to religious orders when he was a senior in high school. He finally applied to the Jesuits, because their response was the lowest‚ keyed of those he received. In 1939, he began the Jesuit training program.

After his novitiate, he studied philosophy at Woodstock College in Maryland, taught French, English and Latin for four years at St. Peter’s Prep in Jersey City, New Jersey, studied theology for three years at Weston College in Massachusetts, and was ordained on June 19, 1952.

In July 1953, Fr. Berrigan was sent to France for a year of study and ministerial work in a small town near Lyons. In France, he met some worker‚ priests who gave him, he later said, “a practical vision of the church as she should be.”

He said there was a “retardation” of his development when, for two months in 1954, he served as a military chaplain in Germany.

Returning to New York in the fall of 1954, he taught French and theology at Brooklyn Prep and led teams of students working in poverty areas in Brooklyn and Manhattan’s Lower East Side.

From 1957 to 1963, he was professor of New Testament studies at LeMoyne College in Syracuse, where he was the most popular and controversial teacher on campus. He worked his students hard and outside of class formed an elite group of followers dedicated to pacifism, civil rights and radical social work.

Older faculty members frowned on “unprofessional” relationship to students and daring liturgical innovations. At the end of the 1962‚ 63 school year, his superiors sent him to Europe for a year. Traveling in Hungary, Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union, he found that “Christians under Marxism have returned to their pre‚ Constantinian situation of being poor, pure and persecuted.”

Returning to New York in the fall of 1964, he began involvement in protest against the war in Vietnam. He helped to found the controversial Clergy and Laity Concerned About Vietnam.

In November 1965, the Jesuit superiors sent him to Latin America in what was described as a reporting assignment for Jesuit Missions magazine. His supporters interpreted the assignment as an attempt by the New York Archdiocese to silence him.

In March 1966, Fr. Berrigan returned to New York and anti‚ war activities. He was the author of more than 16 books of poetry and essays.

Later in life, his work focused ministering to people with AIDS in New York City. He also visited Zuccotti Park in New York to support the brief Occupy Wall Street movement in 2012.