SANTO DOMINGO, Dominican Republic — Heroin and painkillers plague the streets of U.S. cities and small towns. Mexican drug cartels have turned swaths of that country into battle zones. In South Africa, young people are getting hooked on a drug made from a medication meant to fight HIV.

Around the globe, a worldwide addiction to illicit drugs is fueling violence, human trafficking, a proliferation of guns, organized crime and terrorism, the Vatican has said.

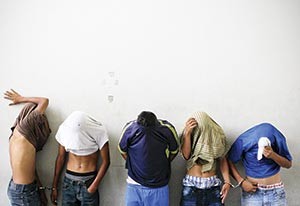

Barrio 18 gang members accused of killing a bus driver in San Salvador, El Salvador, are presented to media July 29, 2015. (CNS photo/Oscar Rivera, EPA)

Now, as the U.N. General Assembly prepares to meet April 19-21 for a special session on the issue, the church is calling on governments and civil society groups to address a problem that has existed for decades but continues to morph and pose new threats.

“From poor rural workers in war-torn zones of production to affluent metropolitan end-users, the illicit trade in drugs is no respecter of national boundaries or of socioeconomic status,” Msgr. Janusz Urbanczyk, Vatican observer to U.N. agencies in Vienna, wrote in the statement. “International solutions require therefore, that effective efforts be indeed focused in zones of production but must also address the underlying causes for the demand in illegal drugs.”

The Vatican position puts it at the center of a tense policy that will play out at the highest levels of the United Nations.

On one side, governments like Guatemala, Colombia and Mexico, which requested the U.N. session, are pushing for new policies, such as improved treatment, providing assistance to grow different crops for farmers who cultivate illicit drugs and alternatives to incarceration for drug users. On the other hand, powerful U.N. members, including China, Russia and Egypt, remain in favor of the prohibitionist war on drugs.

“The Catholic Church is clearly calling for a public health approach, which is similar to the position the U.S. government has taken,” said Coletta Youngers, a former church worker in Latin America and senior fellow at the Washington Office on Latin America, which is in favor of reforming drug policy. “At the same time, I find a lot of the language inflammatory, particularly that it still maintains support for criminalizing drug use.”

On March 29, U.S. President Barack Obama reiterated that his administration wants more treatment options.

“The most important thing to do is reduce demand. And the only way to do that is to provide treatment — to see it as public health problem and not a criminal problem,” he said.

Meanwhile, drug addiction and violence related to drug trafficking is affecting nearly every area of the world, including Central America and Mexico, where spiking homicide rates are pushing residents to flee to the United States.

Mexico launched a crackdown on drug cartels and organized crime 10 years ago but has been plagued by violence ever since, with more than 100,000 dead and 20,000 people missing. Criminal groups have gotten smaller as their leaders are captured or killed and such groups subsequently have taken up activities such as extortion and kidnapping.

The groups also get into small-time drug dealing, another source of violence as they dispute territories. Father Robert Coogan, prison chaplain in the city of Saltillo, a northeastern Mexican city near Monterrey, recalls having a stream of new inmates, previously involved in small-time drug dealing, arrive in the late 2000s with stories of the police raiding their homes and planting evidence.

Drug use increased in Mexico at around the same time, he said. Analysts attribute that to cartels paying their underlings in drugs to be resold.

“I wish people would look more at the society we have that makes people want to do drugs,” Father Coogan said. “Rather than try to prohibit from doing certain things, I would want a society where people wouldn’t feel the urge to do these self-destructive things.”

Governments and civil society groups are grappling how to deal with the scourge: from Argentina to Afghanistan, where poppy, the heroin opium precursor, has become a cash crop for the Taliban; from South Africa to Lake Orion, Michigan, where Robert Koval runs Guest House, a residential rehabilitation facility that has been treating clergy and men and women religious for 60 years.

“I think attention to the issue has spiked in recent years because there’s this question on how to get your arms around a problem that is so rampant,” said Koval, the facility’s president and CEO. Guest House treats about 70 people a year.

Koval said the problem has morphed in recent years as more people have become addicted to opioids, including prescription painkillers, which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says has led to an epidemic of drug overdoses. In 2014, more than 28,600 deaths were caused by opioid overdoses, triple the number from 2000, according to CDC figures.

Those being treated are also becoming younger, Koval said. “It’s what you see in the general population, with drug abuse increasing among young adults.”

Drug addiction among young adults is a problem Cardinal Wilfrid Napier of Durban sees across South Africa, where HIV patients are being robbed of their medications, which are used to make an addictive drug called whoonga.

“The brokenness of the people I saw recently in an outreach clinic and the fact that most of them were teenagers or in their 20s hit me hard,” Cardinal Napier said of a trip to the coastal city of Durban, where drug abuse is the largest problem after disease related to malnutrition and HIV.

The Vatican’s call to improve health care services would help in places like Kenya, where there are too few practitioners to serve the country of 44 million, particularly in rural areas, said Bishop Emanuel Barbara of Malindi.

“Kenyans have become obsessive about taking drugs as the only way to heal,” he said. That’s a problem because medication widely banned in other countries is fully available in Kenya and many “fake drugs” can be found on drugstore shelves.

Luis Lora said there were few treatment options in Ozama, a hardscrabble neighborhood in Santo Domingo, when his alcoholism gave way to a crack cocaine addiction that cost him his marriage and his job as a bus driver.

“There was nowhere to go for help, and it was an embarrassment for me to talk about it with the people I knew,” he said.

Lora, who eventually entered a rehab facility, said that others he knew, “never got help.”

While countries such as Portugal and the Netherlands have long since decriminalized drug use, the debate has only more recently come to the Americas. In recent years, nearly half of U.S. states have passed laws legalizing marijuana use in some form, predominantly for medical use. And Mexico, Uruguay, Argentina, Ecuador, Colombia, Brazil, Guatemala and Honduras have debated liberalizing drug laws or decriminalizing drug use.

When the Mexican Supreme Court ruled in November in favor of four petitioners seeking an injunction to grow and consume marijuana for recreational reasons, Catholic leaders condemned the decision as putting Mexico on the path to legalization. An editorial in the Archdiocese of Mexico’s weekly magazine said it would move the country “toward individual destruction.”

Pope Francis has taken a hardline approach against any forms of drug legalization, including recreational drugs.

“Drug addiction is an evil, and with evil there can be no yielding or compromise,” he said at the International Drug Enforcement Conference in Rome in 2014.

In the pope’s home country, Argentina, Father Jose Maria di Paola, who works with drug addicts in the shanties of Buenos Aires, said drug legalization would do further harm to the poor.

“Why is this our position on legalization? Because we live in marginal and poor environments impacted by drugs. In these places, it’s synonymous with death. It has nothing to do with recreation,” he said in a 2015 interview. “It has nothing to do with morality. It has to do with an analysis of the reality.”