VATICAN CITY — Salvadoran Archbishop Oscar Romero, who will be beatified in San Salvador May 23, has become a symbol of Latin American church leaders’ efforts to protect their flocks from the abuses of military dictatorships.

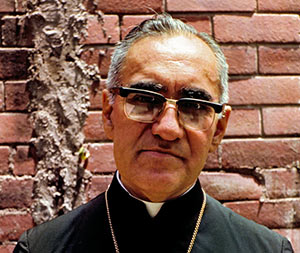

Salvadoran Archbishop Oscar Romero is pictured in a 1979 photo in San Salvador. (CNS photo/Octavio Duran)However, his life and the 35 years it took the Vatican to recognize him as a martyr also reflect decades of theological and pastoral discussion over the line dividing pastoral action from political activism under repressive regimes.

Salvadoran Archbishop Oscar Romero is pictured in a 1979 photo in San Salvador. (CNS photo/Octavio Duran)However, his life and the 35 years it took the Vatican to recognize him as a martyr also reflect decades of theological and pastoral discussion over the line dividing pastoral action from political activism under repressive regimes.

Archbishop Romero was assassinated March 24, 1980, while celebrating Mass in the chapel of Divine Providence Hospital in San Salvador, the city he served as archbishop for three years.

The intense turmoil in El Salvador coincided with a period of intense questioning within the church as pastors in countries under military dictatorships, civil war or communist oppression tried to find the best ways to be faithful to their mission of ministering to their flocks while defending their rights.

The Vatican made frequent calls in those years for priests and bishops, especially in Latin America and in Africa, to stay out of partisan politics. But repressive regimes easily decided churchmen who denounced widespread human rights abuses were meddling in politics.

Jesuit Fr. James R. Brockman, author of a biography of the archbishop, like many historians and supporters of Archbishop Romero’s beatification, said that when Bishop Romero was chosen as archbishop of San Salvador in 1977, he was known as a “conservative” and there was a widespread assumption that he would not directly challenge the country’s rulers. His background was not that of a political activist.

Oscar Romero was born Aug. 15, 1917, in Ciudad Barrios, the second of seven children. Although not considered poor, the family did not have electricity or running water in their home, and the children slept on the floor. Oscar began working as a carpenter’s apprentice when he was 12 years old, but then decided to enter the minor seminary and continue his formal education.

Once he finished his studies at the San Miguel minor seminary, he transferred to the major seminary in San Salvador and was sent to Rome where he studied at the Pontifical Gregorian University. He was ordained to the priesthood April 4, 1942, in the chapel of the Latin American College.

Returning to El Salvador in 1944, he worked as a parish priest in the Diocese of San Miguel, later becoming secretary of the diocese, a position he held for 23 years. During that time – long before becoming archbishop of San Salvador and famous for the radio broadcasts of his homilies – he convinced local radio stations to broadcast his Sunday Masses and sermons so that Catholics in more rural areas could listen and grow in their faith.

He served as rector of the interdiocesan seminary in San Salvador, executive secretary of the bishop’s council of Central America and Panama and as editor of the archdiocesan newspaper, Orientacion.

In 1970, when the priest was 52, Pope Paul VI named him an auxiliary bishop of San Salvador. Four years later, he became bishop of Santiago de Maria, the diocese that included his hometown of Ciudad Barrios. Social and political tensions in El Salvador were growing worse; when five farmworkers were hacked to death in June 1975 by members of the Salvadoran National Guard, then-Bishop Romero consoled the families and wrote a letter of protest to the government.

“Before Romero was archbishop for a month, his deeply admired friend, the Jesuit Rutilio Grande, was killed,” wrote Thomas Quigley, a former official at the U.S. bishops’ conference, in the foreword to the English translation of Archbishop Romero’s audio diary.

Fr. Grande’s strong advocacy for the poor as he ministered in rural communities in northern San Salvador strongly influenced Archbishop Romero, say many of those who knew him. The Jesuit used his pulpit to denounce actions of the government and of the death squads in his country, as well as the violence used by some opponents of the government.

After consultation with the priests’ council, Archbishop Romero “ordered only one public Mass celebrated in the archdiocese on the Sunday following Grande’s funeral,” Fr. Brockman wrote in the introduction to the diary. “It turned out to be the largest religious demonstration in the nation’s history and for many a profound religious experience. But it also led to a serious clash with the Vatican’s ambassador, the papal nuncio, who had pressured Romero not to hold the single Mass lest the government think it provocative. It was the beginning of an enduring lack of understanding and support on the part of the nuncio.”

Archbishop Romero continued having his Sunday Masses and homilies broadcast by radio and, increasingly, he used them as opportunities to explain to Salvadoran citizens what was going on in their country and what their response as Christian should be. He always condemned violence and he urged conversion, particularly on the part of members of the government death squads.

Quigley wrote that Archbishop Romero’s homilies “rarely lasted less than an hour and a half” and included his account of “the events of the week,” both good and bad, “proclaiming the good news of the liberating Gospel and, with the prophets of old, denouncing the evils of the day.”

His homilies and his letters to government officials made him a frequent target of death threats and often put him at odds with several of the other Salvadoran bishops and even with Vatican officials who believed he had crossed the line into politics and was placing the church’s pastoral work in jeopardy.

He lived in a small residence on the grounds of the Divine Providence Hospital in San Salvador and frequently celebrated Mass, vespers and benediction there with the sisters who ran the hospital. He was shot and killed in the chapel, a day after he challenged army soldiers for killing their fellow citizens.