As bombs rained from the sky and the scent of burning buildings permeated the air, she covered her ears to suppress the cacophony of gunfire; to cope, 10-year old, Agnes Schwartz distracted herself with thoughts of happier days.

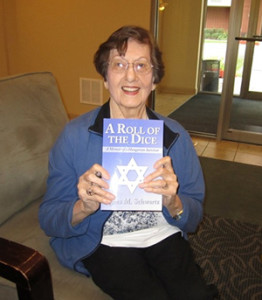

Agnes Schwartz is pictured in a March 1948 photo, taken after the war ended. Agnes’ mother was killed in a concentration camp in 1945, but the young Agnes was sheltered by the family’s Catholic housekeeper, Julia. “She risked her life to save me,” said Schwartz of Julia. (Submitted photo courtesy Agnes Schwartz)

She recalled languid summers in her native Hungary, taking the hour-long train ride to her grandparents’ small farm where they raised chickens, geese and ducks. She often ran through the raspberry bushes, playing among the fruit trees and helping her grandmother harvest vegetables from their garden.

“I loved spending time with them and my childhood could not have been any better,” she said. “It was really idyllic.”

The family lived in an upscale apartment, where Agnes, the only child of Margaret and Eugene, enjoyed playing with her friends, being doted on by her parents, grandparents and aunts and uncles and taking annual summer and winter vacations. Money was never an issue for the small family.

“I was born in 1933, after eight years of marriage for a set of parents who wanted a child badly, and I was the only grandchild for my grandparents,” Schwartz explained. “My mother had an older sister who was married, but childless, and we had a housekeeper, who was also my nanny and a mother figure to me.”

Jewish student in Catholic school

Schwartz enjoyed wearing beautiful dresses made by her aunt, which were the envy of the girls at her Catholic school. At the time, there were quite a few Jewish students enrolled in the neighborhood Catholic school.

“I loved going to the all-girls Catholic school and never felt any [su_pullquote align=”right”]If you go Agnes Schwartz will share her story on Wednesday, April 20 in the Pitman Theatre at Alverno College, noon to 1:30 p.m. The event will include a talk back and copies of her book, “A Roll of the Dice: A Memoir of a Hungarian Survivor” will be available. For those unable to attend the free event, a live stream is available at www.alverno.edu/holocaustremembrance[/su_pullquote]anti-Semitism there,” she said. “We were all treated equally and studied the New Testament with everyone else. A teacher came in once a week to teach the Jewish kids our religion classes and we all got along well in school. After school though, the Jewish kids went one way and the Catholic kids went their own way. We never were able to play together.”

When the bombing began, the Germans forced the family from their apartment into an ugly, yellow building with a large Star of David on the front. They were thrust into a tiny apartment and made to live with another family.

“My grandparents came to live with us, because my parents had heard of atrocities in the outlying areas. So, then, all five of us were living in that tiny apartment in the yellow star building that we shared with the two other ladies,” said Schwartz. “It was so different from what I was accustomed to.”

In many Hungarian cities, Jews were forced to live outdoors, without shelter or bathroom facilities. Food and water supplies were inadequate. Medical care was nearly non-existent. Hungarian authorities forbade the Jews from leaving the ghettos. Police guarded the perimeters of the enclosures.

Individual gendarmes often tortured Jews and extorted personal valuables from them.

Most of their money was taken by the Germans, but even if they had money, food was scarce because the Jews were only allowed to go grocery shopping late in the afternoon, and by then the shelves were clear.

The inhabitants were locked in the house the remainder of the time, and when they did get out to go shopping, they could only purchase certain groceries at shops that sold to Jews.

“My mother and grandmother cooked and made sure we had something to eat, even if the items they were allowed to buy were strange,” said Schwartz.

Not long after Schwartz’s grandparents moved in, her grandfather became ill. They took him to an inferior hospital, left him on a cot and that was the last anyone saw of him.

Star on clothes labeled her Jewish

“I had to wear a yellow star on my clothes every day and though I knew that there was danger in the air, I didn’t truly understand the entire concept,” she said. “My parents did a good job of whispering around me about the conditions so I wouldn’t be scared.”

Schwartz’s world turned upside down with each bomb that fell. She had to

At the invitation of her grandson, Agnes Schwartz began speaking about her experiences during the Holocaust. Telling her story is important for future generations, she said. (Submitted photo courtesy Agnes Schwartz)

stop going to school as the Germans would not allow Jewish children to be educated. Finally, the Germans took her parents and she was left to live with her grandmother.

“My grandmother walked around wringing her hands and kept wondering what would happen to their child, as I was the only child in the whole family,” said Schwartz. “One day, my housekeeper, who was a wonderful Catholic lady, picked me up, and hid me at her apartment building and I instantly became a Catholic child, her niece.”

To blend in, Julia, the housekeeper, gave Schwartz her last name, Balazs, and brought the young girl into the basement of her apartment to hide from the violence.

“She risked her life to save me,” said Schwartz. “If she would have been found out that she was hiding a Jewish kid, it would have meant danger to both of us.”

Approximately 200 people were crammed into the basement of the five-story apartment building which had no running water, heat and bathroom facilities. Julia would run upstairs to her apartment between bombings to bring down beans, potatoes and smoked meat to eat during the day. No one could work or go to school.

“During the night, they would empty the toilet bucket out by candlelight,” explained Schwartz. “I was so scared.”

New Testament knowledge came in handy

For months, Julia and Schwartz lived in the dark basement, blending in as aunt and niece among the others who also called the basement home. Her knowledge of the New Testament came in handy as it allowed her to blend in and pray aloud from the Bible with others.

“There was no communication when the war was over and no telephone or electricity,” said Schwartz. “Finally, my father came to get me and I lived with him.”

Her father was saved by Raoul Wallenberg and hidden in one of his safe houses.

Life slowly resumed; Schwartz went back to school and her father got his business back. They first learned about the death of her grandparents and uncle and aunt who had been living in the ghetto. One day, Schwartz’s father came home from work and was crying.

Devastating news about mother

“He sat me down and told me that a lady came in the store who was in a camp with my mom and told him that my mother died on Jan. 13, 1945 at the Bergen Belsen concentration camp,” she said. “I didn’t believe it. I kept telling my father that my Mommy loved me and she would be coming home to me. But she never did. I just couldn’t believe that she left me.”

After the war, like many other Jewish people, Schwartz and her father changed their last name to a more Hungarian sounding name in order to blend in.

Eventually, they moved to the United States, where her father was later diagnosed with Tuberculosis. He was transferred to Winfield Sanitarium in Illinois, and Schwartz stayed with her aunt and uncle and their family.

“My father was discharged when I graduated grammar school, but he couldn’t assimilate so he went back to Europe and I was truly orphaned. I had a lot of trouble assimilating, too, and remembered that I never felt good at anything,” she said.

Not long after moving back to Hungary, Schwartz’s father married a woman with two children – one was a little girl. Again, Schwartz felt replaced.

“I ended up marrying the first boy who came into my life, and threw away a scholarship to nursing school. I just needed to be number one again in somebody’s life,” she said.

Married at 18, she and her husband had three children. The marriage lasted 15 years, until her husband became mentally ill. In addition to her three adult children, Schwartz has four grandchildren and four great grandchildren. The children have helped her move beyond the hell she endured, she said, and her life is happily entwined with theirs.

For 50 years, Schwartz, who lives in Skokie, Illinois, kept the horror of her childhood tucked in the wounded space of her heart until one of her grandchildren, studying the Holocaust in eighth grade, asked her to come speak to his class.

Sharing story important for future generations

“That was what opened up the door for me to speak, but I had a hard time convincing myself to go ahead, but I did it. Now, I speak at least a couple of times a month,” she explained. “I speak not because I enjoy telling my story, but it is so important, especially for the young people who will be tomorrow’s citizens. Anti-Semitism is running rampant in Europe, and Hungary is mostly anti-Semitic. I have never been back and I have no desire to go back. There is nobody there. The cemetery plot where my family was buried was desecrated. My opinion of Hungarians is not so good either; they welcomed the Germans in our country with open arms. My father’s customers suddenly acted as if they didn’t know him. Everyone was so scared of what would happen and were afraid for their lives. It was a terrible time.”

Though the war is long over, the agony remains in Schwartz’s heart. She admits she struggles with hatred for what was done to her and her family.

“I have hatred for that generation of Germans and will never stop that, but I don’t dwell on the hate and have gotten beyond that,” she said. “I cannot forgive the ones who have killed 6 million people and for how they have ruined the lives of those of us who have survived.”

Her faith has also wavered due to the atrocities done and for the many unanswered questions that plague her.

“I am still looking for the God who was there back in Moses’ time and saved his people,” she said. “I don’t know why he didn’t interfere when 6 million Jews died. I have very little faith. People either turn away or get more religious who live through something like this. I am one of those who turned away. I love my people and care a great deal about Israel, but where was this wonderful God who allowed this to happen?”

Schwartz has a motto when it comes to the Holocaust.

“I say, ‘Never again;’ we can never, ever let this happen again,” she said. “I am so happy that my children are in America. Even with all of the problems we have here, this is still the best country in the world. I truly love this country.”