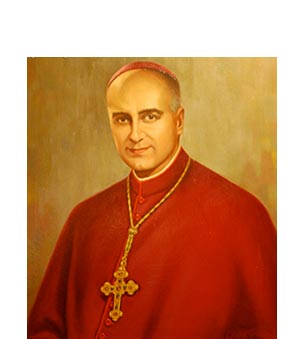

Fifty years ago, on April 9, 1965, Cardinal Albert Meyer – the only native son to have led the Milwaukee Archdiocese – died of brain cancer. Cardinal Albert Meyer, the only Milwaukee native to have led the Milwaukee Archdiocese, is pictured in this portrait, a likeness of him that hangs in the first floor of the Cousins Center. April 9 is the 50th anniversary of his death.

Cardinal Albert Meyer, the only Milwaukee native to have led the Milwaukee Archdiocese, is pictured in this portrait, a likeness of him that hangs in the first floor of the Cousins Center. April 9 is the 50th anniversary of his death.

“He was a great gift of the archdiocese to the universal church, a very exemplary churchman,” noted Fr. Steve Avella, history professor at Marquette University, in a telephone interview with the Catholic Herald. “He was not an authoritarian, not by nature a tyrant.”

CORRECTIONReaders who also receive the print copy of the Catholic Herald may have noticed that our April 9 cover featured this story on Cardinal Albert G. Meyer. However, the photo that accompanied the article was not of Cardinal Meyer. It was of Archbishop Moses E. Kiley. The portrait above, which hangs in the first floor of the Cousins Center, is a likeness of Cardinal Albert Meyer. The Catholic Herald staff thanks all who brought the mistake to our attention and deeply apologizes for the error. |

Fr. Avella, a Milwaukee archdiocesan priest, will preside at a Mass for Saint Francis de Sales seminarians on the anniversary date before addressing clergymen in the Chicago area on the topic of Cardinal Meyer later that day.

The MU scholar devotes numerous pages to the Milwaukee-born prince of the church in “In the Richness of the Earth,” the first of his two-volume history of the archdiocese.

The future prelate was born to German-American parents in 1903, above the family’s grocery store on Milwaukee’s east side, the youngest of five siblings whose two sisters became nuns. Young Albert attended the now defunct Old St. Mary’s grade school and Marquette Academy prior to entering the local seminary, and then finishing his seminary studies in Rome. His first priestly assignment in the archdiocese, as an assistant pastor at Waukesha’s St. Joseph Parish, began in 1930.

Fr. Meyer joined the faculty at Saint Francis Seminary in 1931, and became its rector after six years. He was happy on the seminary faculty, according to Fr. Avella, where he taught Greek, Hebrew, Italian and theology, and remained until he was named bishop of Superior in 1946.

Related article |

He had not aspired to the hierarchy, nor would he seek the promotions that followed.

“He wouldn’t be what Pope Francis would call an ‘airport bishop,’” Fr. Avella said. He was, however, unquestioningly obedient to the wishes of his superiors.

“He was a city boy,” said Fr. Avella. “He was not a rural guy.” Still, he grew “fond of (Superior) and, I think, left with a sense of reluctance” to become Milwaukee’s seventh archbishop in 1953.

Albert Gregory Meyer “was a man of great holiness,” the historian related, “always the first one in the chapel” while stationed at the seminary. “When the students would come in, they’d find him deep in prayer.” Subsequently, in an era quite different from the present, “he was really the last (Milwaukee) archbishop to have a rather unquestioned respect; Meyer still preserved that aura of remoteness.”

Added Fr. Avella, “He also proved to be a very capable administrator. Meyer opened the floodgates for parochial expansion, school expansion” and other postwar projects. Milwaukee’s archbishop “understood that the church was growing and that he had to accommodate” that growth.

In order to do so, the conscientious prelate “worked early (in the morning) and late at night.” The archbishop’s hectic schedule affected his health, resulting in an ulcer and possible episodes of depression early in his five-year tenure. But his health improved and, as Fr. Avella put it, “he resumed his stride.” Beyond his church duties in Milwaukee, the archbishop took in his widowed father, a difficult man in his later years.

Fr. Avella pointed out parallelism in the careers of Cardinals Meyer and Samuel Stritch. Both went from bishoprics in small dioceses (Toledo, in the latter’s case) to become archbishop of Milwaukee and then archbishop and cardinal in Chicago.

Cardinal Meyer was Cardinal Stritch’s immediate successor in Chicago, serving from late 1958 until his death. At the time of transition, Chicago boasted more than 1,400 priests – whose names its new ordinary attempted to learn – and was the largest diocese in the United States, a distinction that currently belongs to Los Angeles.

“There was a real blossoming there, in terms of his willingness to be open to the dramatic situation he found in Chicago,” Fr. Avella said. Chicago’s new spiritual leader faced “racial issues, multiple ethnicities, a distinctively different (more socially minded, less docile) priesthood than Milwaukee, a wide variety of experiences liturgically, an intellectual atmosphere at Mundelein Seminary.”

The “aura of respect accompanied him” to Chicago as he supported the integration of Catholic schools; supported community organizing pioneer Saul Alinsky; and “was one of the first bishops to create what we might call an office of urban affairs.” A reserved man who was certainly not loquacious, Cardinal Meyer was willing to listen to others, the priest noted.

The cardinal’s final years coincided with the Second Vatican Council. According to Fr. Avella, the Meyer stature and credibility enabled him to become “the pre-eminent American leader at Vatican II.”

He “began to have an international respectability,” with Council Fathers from France and Germany, as well as from the United States, enlisting him to act as their spokesman. Cardinal Meyer “really stood out more than anybody as the kind of de facto voice of the American hierarchy,” said Fr. Avella. Moreover, the cardinal “influenced some of the more important council documents.”