While the Catholic Church has made tremendous strides in the past two decades in rooting out clergy sexual abuse, supporting healing for victims, educating people in sexual abuse awareness, and being open and transparent about its actions, those tasked with the safeguarding of children understand that now is not the time for complacency.

June marked the 20-year anniversary of the implementation of the Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People, commonly known as the “Dallas Charter.” The document gave Church leaders and staff clear parameters and protocols on how to deal with issues involving abuse by clergy.

“Good work has been done, but we’re not finished,” said Suzanne Nickolai, the Archdiocese of Milwaukee’s Safe Environment Program Manager. “We cannot rest on our laurels, and we can continue to do good work.”

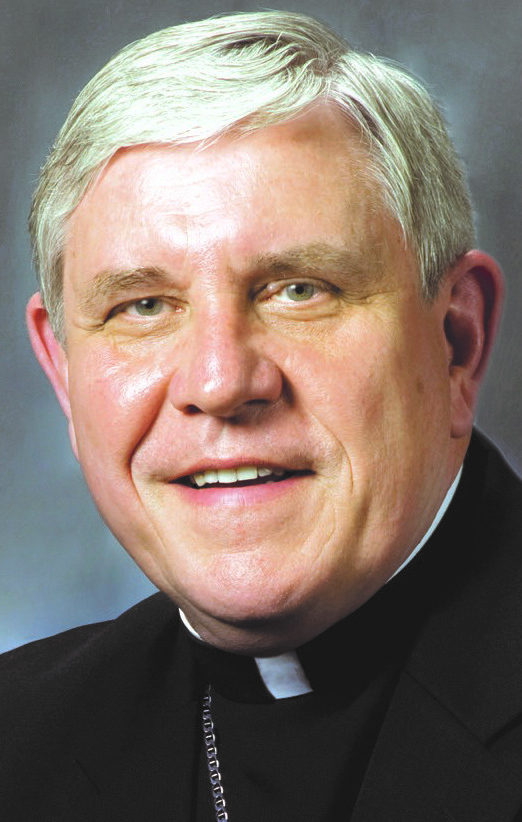

Part of continuing to do good work is the constant reminder to remain vigilant in protecting children within the Church and schools, creating environments where they are free from harm, according to Archbishop Jerome E. Listecki.

“It’s also acting as a witness to the rest of society,” Archbishop Listecki said. “If something good is going to come out of what has been bad in our community, the good can be that we can offer ourselves as an example of how to move forward and how to raise the consciousness of the rest of the society.”

Even before the 2002 gathering of bishops in Dallas, the Archdiocese of Milwaukee had been working on setting in place abuse prevention protocols and procedures, starting with Project Benjamin in 1989. Long before the Boston Globe’s explosive reporting on the subject of clergy sexual abuse, Project Benjamin was designed to “serve victims and survivors of sexual abuse and their families, and also parishes that have been affected by instances of abuse by an employee, volunteer or clergy member.”

“For us, 2002 was just another date on the timeline and there were changes that occurred,” Nickolai said. “Across the United States, there were a lot of dioceses that did have substantial changes because of the Charter. For us, many of the changes in the Charter were things where we were already early adopters.”

In the 20 years since, the Archdiocese of Milwaukee, already at the forefront of the reforms, has trained more than 90,000 clergy, staff, volunteers, employees, teachers and coaches on how to provide a safe environment for children, including beyond the four walls of a school or parish.

In the most recent revision to the Dallas Charter, in 2018, the requirement for training was made more stringent by changing the verbiage to say anyone who has contact with children rather than those with regular contact.

“(The Dallas Charter) became the standard-bearer for how dioceses would respond and implement their response to the sexual abuse crisis,” Archbishop Listecki said. “It gave us a framework, and it gave all the bishops throughout the country a framework. Everybody wasn’t making up their own kind of response. This was an agreed-upon response, which was affirmed by the Pope and by the Vatican.”

Archbishop Listecki said the conference that created the Charter was a bold move by a Church that, at the time, was shaken by revelations of decades of abuse of children by clergy. He said after the Charter was signed, it was up to each of the bishops in the United States to enforce it, and it was an attempt to re-establish the confidence people would have in the Church.

Annual, independent audits of archdiocesan compliance with the demands of the Charter began in 2004 and continue today.

“I don’t know of any other organization that has gone to the extent of developing what the Catholic Church did,” Archbishop Listecki said. “I’m still waiting for the secular society to do the same. We established that standard and we hold ourselves accountable to that standard.”

“In 2002, when they originally signed it, it was a reflection of where we were as a Church and what we needed to do from that point on,” Nickolai said. “Twenty years later, we definitely see the fruits of those efforts, and we see that there has been a lot of progress that has been made. Look at how far we’ve come. We’ve done a lot of good work in the last 20 years, and we’re going to continue to build upon that good work we’ve done.”

In addition to changing the culture of the Church, the reforms outlined in the Charter helped change the culture in the priesthood. Archbishop Listecki said it also took away some of the naivete in the priesthood, shining a light on how seemingly innocent acts could be perceived by onlookers.

“The culture did change,” Archbishop Listecki said. “Maybe the culture needed to change. It gave priests an avenue to secure an environment for children (who) were under their protection.”

Nickolai added, “I think our clergy are much more aware of their interactions and how their interactions are perceived. There is a better understanding in the priesthood that even the mere appearance of something being inappropriate, or the allegation that something is inappropriate, is something they are so conscientious of that they are going to monitor their interactions from that perspective.”

She said some priests have felt anger from strangers as a proxy for the sins of their predecessors and it has heightened their awareness of making sure they hold themselves and their peers accountable.

While Archbishop Listecki and Nickolai said the biggest task for the Church, clergy, volunteers, staff, employees and all those who interact with children is to remain vigilant and not let down their guard, ultimately the document is only as strong as those enforcing and reinforcing the guidelines that have been laid out.

In addition to staying vigilant in prevention efforts, the Church also needs to continue informing the public and the Body of Christ of the efforts it has taken over the past two decades.

“When we go to Mass on Sunday, we’re supposed to take the Gospel message and go forth into the world, not just hold it in our hearts and not do anything with it,” Nickolai said. “It’s the same thing with our abuse-prevention efforts.”

Archbishop Jerome E. Listecki

Suzanne Nickolai