Young Adult

In my experience, one of the greatest gifts of a pilgrimage is a shift in perspective.

Last month, I had the opportunity to go on pilgrimage with my friend to Lourdes for a few days. This was not my first international pilgrimage, so I was prepared for how much things can feel out of control when one is abroad, and how this forces a new reliance on God. From the small details (like when we almost took the wrong shuttle to the airport, but the vehicle broke down, forcing us to get on the right one) to the big ones (like being in Lourdes on the Feast of the Ascension even though we didn’t plan it that way), God has a way of making everything play out much more beautifully than I could have planned. Even the details that were frustrating or difficult have their place in the picture, empowering us to do things we didn’t know we were able to do. The way God provides on pilgrimage becomes a reminder for daily life that he knows what he is doing.

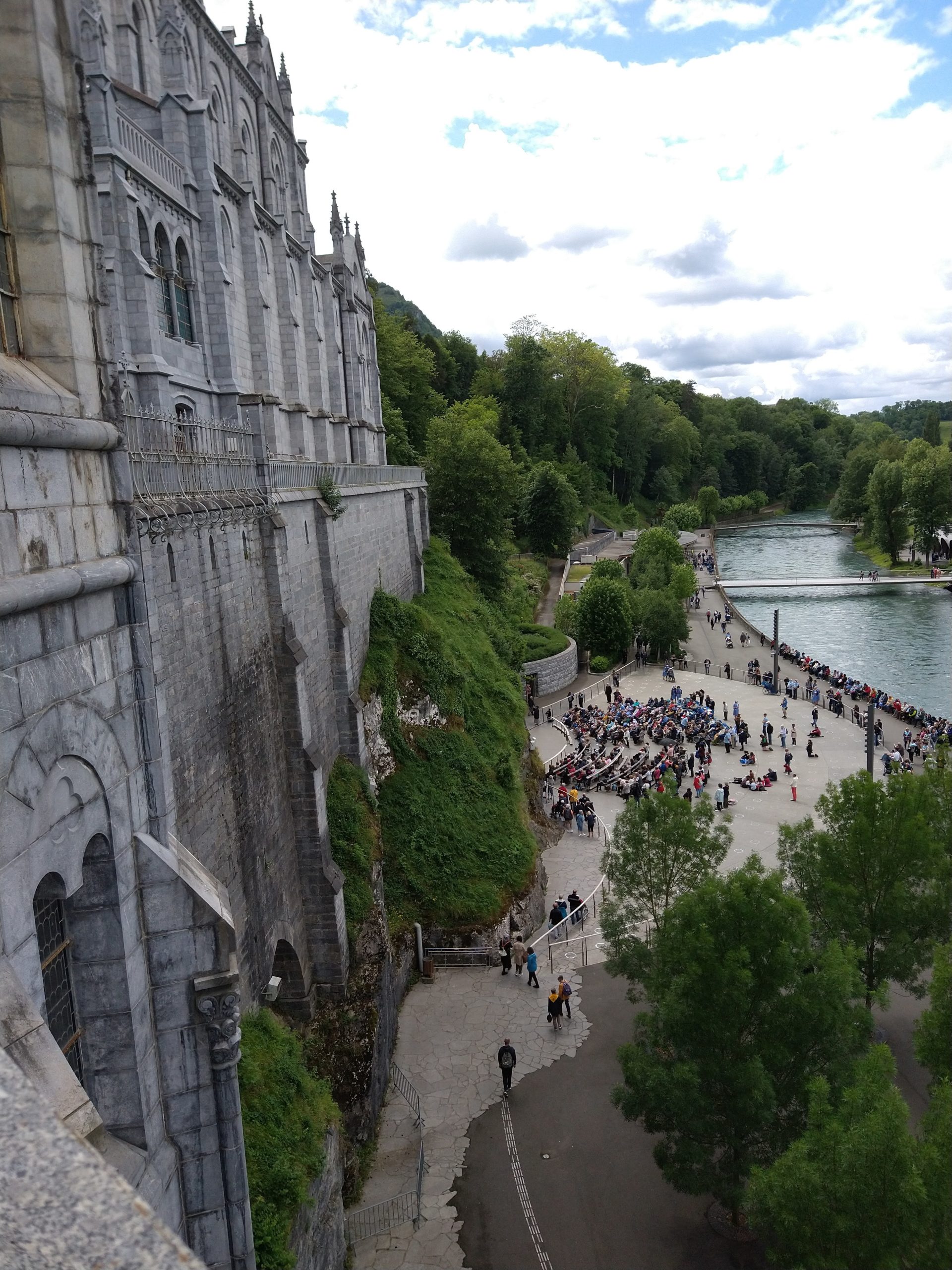

Lourdes is affectionately known as the Catholic Disneyland, and the resemblances are easy to spot. The grand arches and sweeping curves of the magnificent Basilica certainly resemble the castle of a Disney princess and are a far cry from the landfill where the Mother of God first appeared to a poor, uneducated teenage girl named Bernadette. But the grotto where she stood remains, now tucked into the side of the Basilica. And the miraculous spring which Mary revealed in one of her apparitions and has since been the source of many miraculous healings is still sought by countless pilgrims every day. The waters now are freely accessible at any time in at least 40 taps. It is a startling and profoundly beautiful thing to be able to so easily access the miracle of this site.

Also reminiscent of Disneyland is the enormous daily crowds that flock to this place, who come seeking healing. Caravans of wheelchairs constantly receive pride of place, and even the many pilgrims who have no visible need of healing come, bringing the deep burdens and wounds of their hearts. Watching from the upper level as the torches were lit for the nightly rosary procession on the eve of the Ascension, I began to feel the numbers as almost oppressive. Many of those in wheelchairs were elderly and, irrespective of potential healing, their earthly lives would soon be over. Perhaps even sadder were the young people carrying physical handicaps. The onsite medical center has reported a number of verified miraculous healings. Yet, held up against the vast weight of suffering brought daily to this place, those are barely even a drop in the bucket. In the fading light and under the shadow of the old castle that has seen so many centuries full of suffering and death, I pushed away the gathering fear of futility.

The next day was the Feast of the Ascension — the celebration of the day that Jesus returned to heaven, which is also the first time a human body entered into heaven. On the sanctuary grounds, there is a massive underground Basilica built to accommodate liturgies on the scale required by the daily crowds. The architecture is oppressively concrete, with heavy features and small windows. But lining the walls are enormous banners of the faces of the saints, which I found to be incredibly powerful. They made visible a theme that was dominant throughout my pilgrimage: the transformative power of holiness and the presence of the saints with us. Ascension Mass in that underground Basilica was celebrated by at least half a dozen bishops and a small crowd of priests in a wide array of languages. The people around me in the back pews were from all around the world — families and tour groups and retired couples and groups of friends — a microcosm of the universal call to holiness. It was as if everything around me was conspiring to physically remind me how much the only thing that matters is becoming a saint.

That day we also did the Stations of the Cross — beautiful, larger-than-life statues winding their way up the mountain. We wandered the complex maze of buildings on the sanctuary grounds, prayed in the strikingly peaceful Adoration chapel, walked the inside of the grotto with our hands pressed against the very rocks on which Mary stood, drank from and washed in the waters of the miraculous spring, and took part in the daily Eucharistic procession across the grounds. This procession is always led by the Eucharist, followed closely by all of those in wheelchairs.

As my friend and travel companion said, “so many things about being in this space make you unafraid to acknowledge areas you need healing — something those with physical disabilities never have the luxury of forgetting, but also something true for every one of us. The Lourdes environment makes God’s loving care for our hearts feel so tangible, in a way that allows us to let down our guard and be OK with sitting in the parts of our lives that feel unsettled, incomplete and maybe even inadequate, because we know that’s not the end of the story.”

For whatever confluence of reasons, I looked down on the torch-light procession that second night with a shifted perspective. I imagined being able to physically see the deeper impact that this place has every day. How many souls are being touched, re-oriented toward the living God, opening to receive his transfiguring love and living more fully alive, more fully themselves because of it. As profound and beautiful as the physical healings are, they are only a signpost to what we are made for: becoming the full measure of who God meant us to be so that our resurrected bodies can live in the love of God for all eternity.