Catholic Family

Bedtime is a marathon at our house, not a sprint: it takes a long time, it’s as much a psychological challenge as it is a physical one, and I’ve learned you should plan for water breaks.

It’s also a contact sport; one or all of our children, at varying times in their life, have been unable to fall asleep unless they are touching my husband or me. Yes, we’ve read all the books; yes, we understand this is not an ideal sleep situation. Welcome to parenthood — in fact, welcome to life. We rarely encounter the ideal situation here. We just do our best with what the good Lord sends down the pike.

It’s an exhausting, frustrating ordeal, but when it’s all over, when all is finally calm and the little chests are rising and falling with the telltale cadence of sleep, I can’t ever quite bring myself to leave the darkness of their room. Not right away. In fact, I usually stay for quite a while.

I would not call these moments relaxing, or even peaceful. But there is something holy about them nonetheless. Sitting there in the dark, I begin to look inward. I never have time during the day to stop and think. It’s all go, go, go. But these nighttime interludes force me to reflect. My body is so tired, and the darkness envelops me like a pair of arms.

In those moments, I think about the kind of mother I am, or at least the kind of mother my children see. I think about the things I try to do well, and the things I decide are not worth the effort. Inevitably, in these moments, I spend a good deal of time contemplating the “shoulds” of life — the choices I should make, the food we should be eating, the clothes we should be wearing, the behaviors the children should be adopting. I think about the postcard-perfect mother I always thought I would be. I think about the reality of the mother I am, and the distance between the two.

As I listen to the gentle breathing of my babies, I become acutely aware that they are not mine at all. They are on loan. I am only a steward.

Motherhood, I have come to understand, is a penitential season. It is a time when we are not only obliged to take up our burden, we are obliged to love it, to celebrate it. It is a time of fasting from so many of the activities, comforts and priorities that defined our pre-parenthood existence. It is abundant in opportunities for works of charity and self-denial. It is a time of self-scrutiny and heavy sighs and resolutions to do better.

I always begin Lent much like I began parenthood: very sure that I am in charge, and very sure that it will go well. Come Holy Week, I am the same version of myself that sits in the dark at the bedsides of my children: humbled, tired, confused, in awe.

I always expect great things of myself in Lent, and only accomplish very small things — if I accomplish anything at all. The sacrifices I make never go the way I want them to, for I make them in such a slipshod, human way. They have less effect than I thought they would. My soul looks disappointingly similar on Good Friday to how it did on Ash Wednesday, at least from my perspective.

Lent, like motherhood, is a series of penances imperfectly executed, leading to an absolution of which I never feel worthy.

Yet, when I make it to the Easter Vigil and the light slowly spreads through the church, candle to candle, flame to flame, I feel the same sense of peace, gratitude and joy that I do at the end of a very long and very discouraging day, when I sit in the darkness of my children’s bedroom and watch their chests rising and falling.

In both moments — beholding the flame, beholding the children — I think to myself: “Who am I, that all this should be mine?”

In both seasons, Lent and motherhood, when I lose my footing, it is because of the same fault: pride. Overdependence on my own abilities. Because at the end of Lent, whether I realize it or not, I expect to be the postcard-perfect disciple. I expect to be “fixed” by my own sacrifices and my own offerings. But that could never happen.

What I have learned from the penitential seasons of life is this: I am never enough. I can never be enough. I can never deserve what I have — not the children I was sent or the salvation I was offered. Like the Israelites of old, I cannot make a perfect sacrifice. I need someone else to do that.

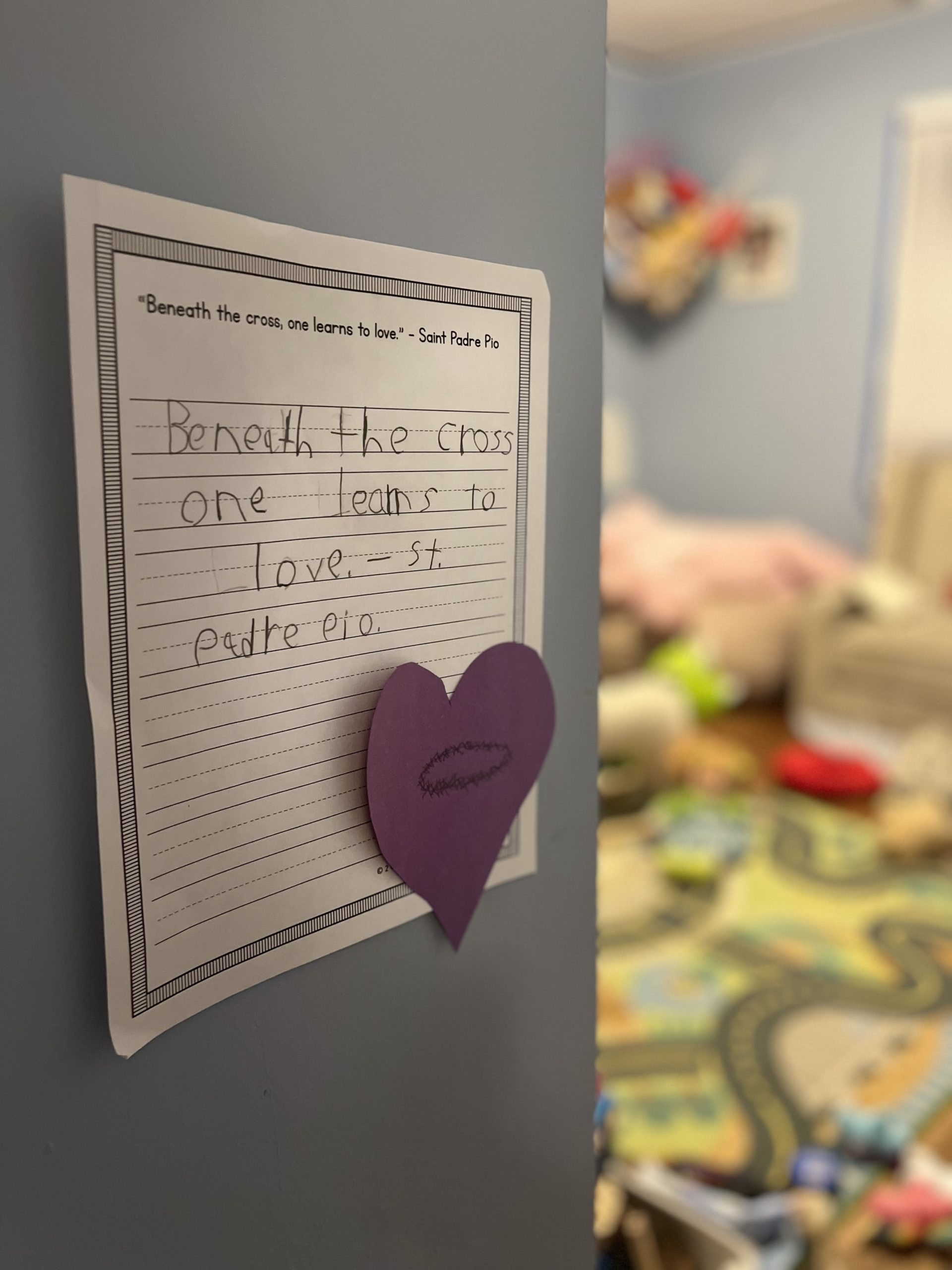

A long and discouraging day as a parent can still end with peace and comfort, writes Colleen Jurkiewicz. (Submitted photo)